~Updated September 2017~

The California State Parks describes the California Missions Trail importance as "humble, thatch-roofed beginnings to the stately adobes we see today, the missions represent a dynamic chapter of California's past. By the time the last mission was built in 1823, the Golden State had grown from an untamed wilderness to a thriving agricultural frontier on the verge of American statehood."

LEFT: The San Juan Capistrano Mission in Orange County, circa 1910. (Photograph, Library of Congress)

The history represented by the Spanish missions trail is of European settlement, but it is not the only mission trail in California. There is a missing chapter, pages torn out and forgotten, as the State transitioned from an agricultural frontier toward the social change and urban development of the 20th Century.

In 1885, the first Japanese mission in California marked the beginning of an effort for a new group of pioneers to establish communities as they assimilated to American life. It is integral to the dawning of Pacific Rim interaction and migration.

While the twenty-one Spanish Franciscan missions were stationed approximately 30 miles apart---a day or two ride by horseback---the Japanese missions sprang up in communities where immigrants established themselves for work. In Orange County, work in the early 1900s focused in the celery and chili pepper fields surrounding the Wintersburg Village, before gradually moving south and east.

.jpg) In contrast to the Spanish missions, there was no effort to create a labor force from Native Californians or other populations; in this case, the missions were established by the those already laboring in the fields. And, unlike the Spanish missions, the Japanese missions were not representative of a dominant, conquering culture.

In contrast to the Spanish missions, there was no effort to create a labor force from Native Californians or other populations; in this case, the missions were established by the those already laboring in the fields. And, unlike the Spanish missions, the Japanese missions were not representative of a dominant, conquering culture. RIGHT: The Wintersburg Japanese Presbyterian Mission, circa 1911-1912. (Photograph courtesy of Wintersburg Presbyterian Church) ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. ©

These were the missions of those who faced exclusion, discrimination and a succession of laws that prevented citizenship and land ownership. These were the missions that followed their communities into the forced evacuation and confinement of World War II, safeguarding their congregants' belongings and providing comfort for those inside relocation camps. These were the missions whose clergy were incarcerated along with their congregations. These were the missions who helped their flock return to West Coast communities after World War II, providing both shelter and guidance as they rebuilt lives.

The surviving Japanese mission sites are representative of those subjected to the largest forced evacuation and confinement in American history. They witnessed an often intense and painful struggle for civil liberties and citizenship in America, and were instrumental in the remarkable post-World War II recovery of Japanese Americans.

ABOVE: A cenotaph for Dr. E.A. Sturge in the Japanese Cemetery in Colma, California, notes "he gave us his very homes for our use in San Francisco and San Mateo." Sturge helped establish fourteen Japanese Presbyterian missions on the Pacific Coast.

In loving memory of Dr. E. A. Sturge

Physican, author, artist, and poet

Spiritual father to us

He loved the Japanese

For forty eight years onward from 1886 he dedicated his life to us

He established fourteen Japanese Presbyterian churches on the Pacific coast

~Cenotaph for Dr. E.A. Sturge, Japanese Cemetery, Colma, California

Ernest Adolphus Sturge, M.D., Ph.D.

In San Francisco, the Christ United Presbyterian Church remembers E.A. Sturge each year on his birthday, referred to as "Sturge Sunday." The mission was organized in San Francisco on May 16, 1885 as the First Japanese Presbyterian Church in San Francisco. It is the oldest Japanese Christian church in America.

ABOVE: Ernest Adolphus Sturge and his wife with a group of mission assistants in northern California. (Image, The Spirit of Japan, 1903)

The year after its organization, Sturge was appointed by the national Presbyterian Church in 1886 to serve as Missionary of the Presbyterian Board to the Japanese in California, developing a statewide mission plan. His biography notes the Sturges "cheerfully taught classes of Japanese students who were anxious to learn the English language." The couple is acknowledged as among the first to initiate mission efforts in the Japanese immigrant community in America.

RIGHT: Mrs. C.H. Sturge, wife of Ernest Adolphus Sturge and his partner in the Japanese mission efforts. (Image from The Spirit of Japan, 1903)

Sturge was not an ordained minister, but held two doctorates: one as an M.D. and the other a Ph.D. He had traveled through Asia, working as a medical missionary in Siam (Thailand) and in China.

His time in Japan and with the Japanese community in America---originating in San Francisco---became the catalyst for his life's work.

Henry Collin Minton, a chair at the San Francisco Theological Seminary from which graduated some of the first Japanese clergy, wrote "there is no more interesting missionary work on this continent than that which has been quietly but efficiently carried on all these years among the Japanese community" (in California).

In 1903, Sturge was honored by the publication of a book entitled, The Spirit of Japan, which included a selection of essays from colleagues and poetry by Sturge. It was published by the Japanese Young Men's Christian Association as a surprise to recognize his "indefatigable zeal and painstaking kindness"and in "recognition for the years of ernest toil for the education and advancement of the Japanese."

LEFT: Ernest Adolphus Sturge, M.D., Ph.D. (Image from The Spirit of Japan, 1903)

One of The Spirit of Japan authors and editors, Reverend Joseph K. Inazawa submitted the volume to the Library of Congress, and it was entered officially by an Act of Congress in 1903.

Rev. Inazawa was the first clergy at the Wintersburg Japanese Presbyterian Mission in 1910. He and his wife, Kate Alice Goodman, were the first to live in the manse at Historic Wintersburg.

Inazawa writes of Sturge in The Spirit of Japan, "our beloved doctor has been my esteemed guardian, admirable teacher, confidential friend and elder brother..."

RIGHT: Reverend Joseph K. Inazawa, the first clergy officially assigned to the Wintersburg Japanese Presbyterian Mission as the first mission building opened in 1910. (Photograph courtesy of Wintersburg Presbyterian Church) All rights reserved. ©

Another entry in the book is from Kisaburo Uyeno, His Imperial Japanese Majesty's Consul in San Francisco, who noted by then Sturge had been living and working with the Japanese in America for twenty years.

"Since the opening of friendly relations with America, our people have been immigrating into this vast and wonderful country; and we are, today, nearly 20,000 strong. Many of our pioneers have encountered great difficulties and perplexities," writes Uyeno. "Some have left behind them only their graves to narrate the tale of their careers, and all have come with the feeling that they were among 'a strange people and under strange stars.' "

ABOVE: Portraits of those involved in California's Japanese mission effort, including Dr. E.A. Sturge (#1) and Wintersburg Japanese Presbyterian Mission clergy, Reverend Joseph K. Inazawa (#5). (Image from The Spirit of Japan, 1903)

"But as we often see beautiful flowers blooming here and there among the briers and dried thorns, so these people have found on this stranger soil many kind hearts and great souls, who have shown them consideration and sympathy," continues Uyeno. "For them we are greatly indebted for our prosperity on this coast and our friendship with the people here. Among these kindly Americans, Dr. Sturge stands very prominent."

Writing from Tokyo, Japan, Reverend Fumio Matsunaga says of Sturge that "though an American gentleman he resembles a Japanese knight of medieval age." The admiration was mutual. Rev. Matusnaga had once presented Sturge with a copy of Bushido, The Soul of Japan by Dr. Inazo Nitobe, and recalled how Sturge was taken by the explanation of the Japanese code of honor.

Published in 1903, The Spirit of Japan debuted one year before the founding of the Wintersburg Mission in 1904. At the time of publication, there were four Japanese Presbyterian missions in California: San Francisco, Watsonville, Salinas and Los Angeles.

The next year, the Wintersburg Mission was founded with the help of Reverend Hisayoshi Terasawa, who had traveled down from San Francisco---where Sturge was living---to work with Presbyterian and Methodist missionaries. He began holding services in a barn in Wintersburg Village.

LEFT: Two of the four California Japanese missions established as of 1903---one in Watsonville and the other in Los Angeles---are shown in The Spirit of Japan, published one year before the fifth mission, the Wintersburg Mission, was founded in 1904. The other missions at that time were in San Francisco and Salinas, California. (Image, The Spirit of Japan)

Charles Furuta was among Rev. Terasawa's first congregants, the first Japanese baptized Christian in Orange County, and became a trustee and elder of the Mission. His donation of land in Wintersburg Village fostered the Mission's growth into an official church in 1930 and allowed for the second, larger church building in 1934. This places Charles Furuta among those pioneers who helped establish and support the Japanese mission trail in California.

Wintersburg Village

By 1902, seventeen years after the first Japanese Presbyterian Mission was established in northern California, the Presbyterian and Methodist Evangelical churches in nearby Westminster had taken note of Orange County's growing Japanese community. Rev. Inazawa was sent to investigate. By 1904, Rev. Inazawa and Rev. John Junzo Nakamura met with Rev. Terasawa, leading to the founding of the Wintersburg Mission.

At that time, there was no Presbytery established in Orange County. The Los Angeles Presbytery had no funds, leaving the Wintersburg Mission support to the local community. In an interfaith effort, nearby Presbyterian and Methodist congregations contributed, as did the Christian Endeavor Union of Orange County. Donations for the first chapel came from the surrounding farmland, including from some of Huntington Beach's and Westminster's prominent pioneer families.

Rev. Nakamura stayed on to oversee the building of the Mission and manse, with "the aid of our countrymen and some good American friends."

ABOVE: The opening of the Mission on May 8, 1910, with the manse to the left and in the background, the Terahata home that had been moved temporarily to the property. At the center of the crowd along then-country road Wintersburg Avenue can be seen Charles Furuta, on whose land the Mission stood, and Dr. E. A. Sturge. (Photograph courtesy of Wintersburg Presbyterian Church) ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. ©

Sturge attended the opening ceremony of the Wintersburg Mission on May 8, 1910, to see the work of his protégé, Rev. Inazawa, as did Rev. H.C. Cockrum of Westminster and five other local clergy. It was a large gathering for the little Wintersburg Village.

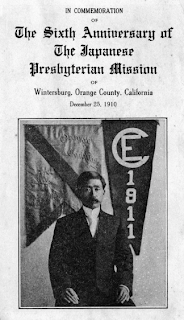

In a December 25, 1910, pamphlet marking the sixth anniversary of the Mission's founding, Rev. Nakamura describes how he made the circuit in rural Orange County, a trip that today would take a day took a week to complete.

LEFT: Japanese farmers on horseback at Irvine Ranch, Orange County, circa 1920. (Photograph snip courtesy of California State University Fullerton, Center for Oral and Public History PJA 497) ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. ©

"Last summer, I tried a fortnight's campaign of gospel preaching, during which I traveled over two-hundred and twenty-five miles, visited forty families and camps, preached to four-hundred and fifty souls, distributed three-hundred and sixty copies of the Gospel of Matthew and sold eighteen copies of the New Testament," writes Rev. Nakamura, who adds that he converted four souls.

Rev. Nakamura would have traveled by horseback through the farm fields, ranches and open land to reach the scattered Japanese immigrants, riding through the tules of the peatlands. His account also makes note of the annual Christian convention held in Huntington Beach in 1910, at which his group received the Orange County Christian Endeavor Union banner.

Rev. Nakamura would have traveled by horseback through the farm fields, ranches and open land to reach the scattered Japanese immigrants, riding through the tules of the peatlands. His account also makes note of the annual Christian convention held in Huntington Beach in 1910, at which his group received the Orange County Christian Endeavor Union banner."It was entirely unexpected!" writes Rev. Nakamura, who adds that they shared a Thanksgiving meal with"a few American friends" in Orange County afterward. Although noting that "at present our Mission has no permanent resources," he is encouraged they started with "fifteen active members, five associate members, and fifteen friends."

RIGHT: Reverend John Junzo Nakamura with the Young Christian Endeavor Union banner. (Image courtesy of the Furuta family) ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. ©

Rev. Nakamura describes the mission field as including Wintersburg, Bolsa Beach, Smeltzer, Bolsa, Garden Grove, Old Newport, Talbert and Huntington Beach. In 1910, he estimated there were about 300 Japanese permanently living in the area.

Japanese Missions in California

The Presbyterian Japanese Mission trail in California is joined by the early Methodist Evangelical, Episcopalian, congregational Japanese missions and Japanese Buddhist temples established during the pioneer settlement period starting in the late 1800s. Most were established through interfaith efforts, community helping community. Not all have survived the politics and development of California.

As the United States entered World War I in 1917---and after 30 years working to establish Japanese missions in California---Sturge provided an update as part of the Annual Report of the Board of Foreign Missions to the national Presbyterian Church.

"About 90% of the 100,000 Japanese in the U.S. are on the Pacific Coast...there are 66 churches and missions belong to twelve denominations," writes Sturge. "The work among the Japanese on the coast is carried on at San Francisco, Salinas, Watsonville, Los Angeles, Wintersburg, Hanford, Stockton, Sacramento, Monterey, Long Beach. There are 17 unorganized churches or groups and five organized churches..."

LEFT: Viscount Kikujiro Ishii, second from left, visited the United States in 1917 on a special mission for the Imperial government of Japan. Despite California's passage of the Alien Land Law of 1913 and restrictions on immigration, Japan and the U.S. federal government worked to maintain relations on the Pacific Rim. (Photograph, Library of Congress)

This also was the year Viscount Kikujiro Ishii visited the United States on behalf of Japan, as part of a special mission to assure good relations with the United States. He stopped in San Francisco on his way to Washington, D.C., to meet with and address Californians, remarking on the hospitality he had been shown:

In response, California attorney Gavin McNab---who acted as toastmaster for the official state visit and was a member of President Woodrow Wilson's industrial council---invoked the romance of California's Franciscan missions, perhaps not realizing another California mission trail had taken root three decades earlier.

Mapping the Missions

Today, there is a need to put the Japanese mission trail on the map before it is lost to time. Historical missions like the Wintersburg Japanese Mission have been demolished or are in jeopardy. The Wintersburg Japanese Mission---the oldest Japanese mission in most of Southern California---is at risk of being lost forever, as are all six historic buildings at Historic Wintersburg, including the Furuta Gold Fish Farm. We invite our readers to send in the known locations and historical photos of California's Japanese Mission Trail.

ABOVE: Part of the Wintersburg Village community gathering for the dedication of the second church building at Historic Wintersburg, the 1934 Depression-era Church. The occasion also marked the 30th anniversary of the Mission's founding. The diverse crowd represents the support the Mission effort received from the surrounding countryside. (Photograph courtesy of Wintersburg Presbyterian Church) ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. ©

ENDANGERED: The Huntington Beach City Council voted 4-3 on November 4, 2013, to certify the Environmental Impact Report which approves the zone change of Historic Wintersburg from residential to commercial / industrial, and approves the demolition of all six historic structures.

In 2014, Historic Wintersburg was named one of America's 11 Most Endangered Historic Places. In 2015, Historic Wintersburg was named a National Treasure. The property has been noted by the National Park Service as potentially eligible for the National Register of Historic Places under Criteria A, Japanese American Settlement of the American West.

As of September 2017, Historic Wintersburg--owned by Republic Services--remains endangered.

SUPPORT PRESERVATION: Join our Facebook page at https://www.facebook.com/pages/Historic-Wintersburg-Preservation-Task-Force/433990979985360

© All rights reserved. No part of the Historic Wintersburg blog may be reproduced or duplicated without prior written permission from the author and publisher, M. Adams Urashima.

+Cleaned-up.jpg)