ABOVE: Yukiko Furuta inside her home at Wintersburg (Warner) Avenue, circa 1912. (Photo courtesy of Center for Oral and Public History, California State University Fullerton, PJA 313) © ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

Historic Wintersburg continues with Part 4 of 4 of the interview with Arthur A. Hansen. Hansen is Emeritus Professor of History and Asian American Studies at

California State University, Fullerton (CSUF), immediate past director of the CSUF Center for Oral and Public

History (COPH), founding director of COPH’s Japanese American Oral History

Project, and currently serves as a historical

consultant at the Japanese American National Museum.

----------------------------

The interviews with Henry Kiyomi Akiyama, Yukiko Furuta, and Reverend Kenji Kikuchi yielded a wealth of information about the Wintersburg area and, most particularly, the historic structures associated with the Wintersburg Japanese Presbyterian Church and the Furuta family. Hansen provides their narratives below.

Henry Kiyomi Akiyama - From Nagano, Japan to the Wintersburg celery fields

The first of this trio of pioneering Orange County Issei to come to Orange County was Henry Kiyomi Akiyama, who arrived in 1907. Born in 1888 in a village within Nagano Prefecture (the "Japanese Alps" or "snow country" region of Japan), Akiyama emigrated from Japan at age twenty on a student visa.

Part of his motivation for leaving Japan and migrating to the United States was to avoid conscription into the Japanese army. Also, his family did not have much money and he had only an eighth-grade education; he did not foresee a promising future in Japan.

After landing by boat in Vancouver, Canada, Akiyama took a train to Seattle, Washington. There he remained working at a sawmill for six months, following which he moved again to San Francisco, California. The situation was not good in that city, however, since he had arrived there only one year after its devastation by the legendary 1906 earthquake and fire.

LEFT: Matsumoto Castle in Nagano Prefecture, Japan, remains one of the oldest intact castles of the Samurai. The rule of the Samurai came to an end in the Meiji era (circa 1868-1912), which prompted some to leave for America. (Photo, Wikimedia Commons, circa 1904)

When he left Japan, Akiyama intended to go to California. This was because one of his Nagano village relatives, Tsuneji Chino, had gone there two years earlier and settled in the unincorporated southern California agricultural community of Wintersburg (founded circa 1890 by and named after Ohio-born Henry Winters).

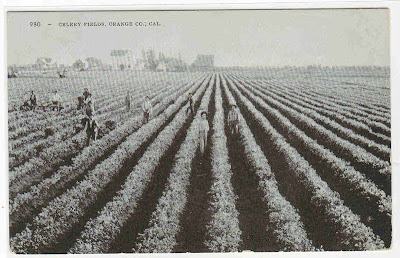

Chino, a well-educated graduate from a teachers' college in Japan, was running a labor camp for Issei working in the lucrative Orange County celery fields. (At the height of production, in the first decade of the twentieth century, nearly 6,000 acres in the County were devoted to celery.)

Mindful that this camp--together with three others in Wintersburg--hired hundreds of Issei workers at harvest time, Akiyama booked train passage from San Francisco to Orange County (a twenty-one hour journey).

In the camp run by Chino, Akiyama labored alongside a work gang ranging between thirty and fifty Issei, most originating from the Japanese prefectures of Hiroshima, Fukuoka, and Wakayama. The Chino-led camp in Wintersburg (vicinity of present-day Springdale Street) was located on agricultural land owned by Ray Moore.

ABOVE: Smeltzer celery train accident, circa 1901, in the area of present-day Edinger Avenue and Gothard Avenue. The soft peat soils were perfect for celery, but not so perfect for trains. (Photo, First American Title)

There was a County celery association organized as early as 1902 by Caucasian celery farmers, like Moore, located in nearby Smeltzer: the Smeltzer Celery Association. The Association--which handled celery shipping for Smeltzer, Wintersburg, and the adjacent community of Talbert--required labor camp bosses to round up the needed agricultural workers.

Each landlord provided his laborers with housing, which was woefully substandard. Because no beds were supplied, the workers spread straw on the dirt floor and slept upon blankets. Once the harvest ended, each laborer rolled up his blanket and carried it away to a boarding house in Los Angeles' "Little Tokyo" district, until receiving a new work assignment.

These workers called themselves buranke-katsugi or "blanket carriers." They worked ten hours daily, Monday through Saturday, and their typical compensation was fifteen cents an hour.

RIGHT: Workers in the Smeltzer celery fields, now present-day Huntington Beach, earned fifteen cents an hour.

Akiyama, though, did not travel back and forth between Wintersburg and Little Tokyo. With completion of celery harvesting--October to February--he remained in his Wintersburg labor camp for the rest of the year to make celery plant beds, grow potatoes and onions, and do a variety of other landlord-assigned jobs.

According to Akiyama, some of the Issei celery workers in the labor camps spent their Sundays attending church. This was possible because in 1904, Reverend Hisakichi Terasawa--a fluent, English-speaking Episcopalian minister and graduate of Cambridge University, England--started missionary work among the County's Japanese immigrants. At first, Reverend Terasawa (whose wife temporarily lived apart from him in San Francisco while working as an immigration office interpreter) organized church services in a barn on the same Wintersburg property he was renting.

Terasawa cleaned out the barn and borrowed chairs from the Veterans' Social Home, a Caucasian institution, for his Issei parishioners. He made the barn into a weekend gathering place for the mostly bachelor men, since they had nowhere else to socialize.

ABOVE: The Reverend and Mrs. Terasawa and family. A graduate of Cambridge University, Terasawa was instrumental in the founding of the Wintersburg Japanese Presbyterian Mission effort in 1904. (Photo, courtesy of Wintersburg Church) © ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

At the time, Japanese aliens could buy land. Reverend Terasawa helped buy five acres in Wintersburg, of which half an acre was set aside for the Wintersburg Japanese Presbyterian Mission. Charles Mitsuji "C.M." Furuta--a prominent Issei supporter of the church project from its inception--owned the remaining four and one-half acres. The Wintersburg Japanese Presbyterian Mission was dedicated in December, 1910. Within two years, it was joined by the manse, or parson's house (circa 1911) and in 1912, a cottage owned by Furuta and his Issei wife, Yukiko Yajima Furuta.

Next to the church in Wintersburg was a store owned by another Issei, Tsurumatsu "T.M." Asari, originally from the Wakayama Prefecture. Akiyama relays in his oral history that Asari came to Orange County in 1903 and was probably the first person of Japanese ancestry to make the County his home.

It was in large part because of the Asari market that Wintersburg became the center of the County's Japanese community, which by 1910 consisted of a year-round community of approximately 20 Issei. At harvest time, many more Japanese came to Wintersburg to work as seasonal laborers. Many of these young Issei had knowledge of Christianity in Japan, accounting in part for their attendance at the Wintersburg Mission. In the case of Akiyama, he converted to Christianity at the Wintersburg Mission in 1913, though he had been associated in Japan with a Christian group centered in Tokyo called Rikkokai.

RIGHT: A gathering in Wintersburg, circa 1910-1915. (Photo, courtesy of Wintersburg Church) © ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

About 1910, Tsuneji Chino (Springdale labor camp) and Shujiro Ohta organized a branch of the San Francisco-based, national Japanese Association. Because of the existence of the celery association in Smeltzer, the local branch was called the Smeltzer Japanese Association, although it met in Wintersburg. Asari told the Association he would build a second floor onto his market--which included a barber shop and pool hall--if they agreed to rent it for their meetings, which they promptly did.

This development enhanced Wintersburg's status as the center of the Japanese community in Orange County. As for Akiyama, he worked for several years at the Asari market and also served as one of the treasurers for the Smeltzer Japanese Association.

In Akiyama's recollection, most of the Japanese living in the Wintersburg-Smeltzer-Talbert area belonged to the local branch of the Association. He recalled the Association functioned like an arm of the Japanese Consulate for the immigrant community, issuing birth certificates, attending to matters relating to the draft status of overseas Japanese residents, mediating between the Japanese and Caucasian community during times of trouble, and coordinating social events, such as picnics and athletic competitions.

ABOVE: Japanese agricultural workers in Huntington Beach celery fields, circa 1920. (Photo courtesy of Center for Oral and Public History, California State University Fullerton, CD1002) © ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

The Association's president was Akiyama's Nagano relative, Chino, who also served in the same capacity for the Central Japanese Association of Southern California for branches in Los Angeles, San Pedro, Garden Grove and Orange. M. Matsushima--who came from the same Nagano village as Akiyama and Chino--served as secretary for the Smeltzer Japanese Association.

After working in Chino's labor camp for two years (1908-1909), Akiyama joined C.M. Furuta and Chino in farming on a crop rent basis on land near the Wintersburg Mission owned by M.C. Cole. Together, the three Issei worked sixty acres on Cole's land for which they received a specified part of the crop as their share. Mainly, they cultivated celery, sugar beets and beans.

Because of Chino's time-consuming Japanese Association responsibilities, most of the actual labor was done by Akiyama and Furuta. By 1912, Chino moved to Talbert and started cultivating sugar beets. Cole--feeling himself too old to farm any longer--persuaded Akiyama and Furuta to take over his farm. In that same year, Furuta sailed to Japan to marry Yukiko Furuta (née Yajima) of Hiroshima.

Yukiko Furuta: A bride at seventeen and a new life in Wintersburg

The interview with Yukiko Yajima Furuta nicely picks up the thread of Akiyama's interview narrative.

ABOVE: Yukiko and C.M. Furuta at their new home on Wintersburg (Warner) Avenue, circa 1912. (Photo courtesy of Center for Oral and Public History, California State University Fullerton, PJA 311) © ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

Born in 1895 as the oldest daughter in a family of five children, her family before her birth was a good Samurai family. However, because her father had spent all the family's money, the Yajima family was not wealthy during her childhood. In that interval--when the population of Hiroshima (on the Ohta River) was 130,000--her father was in the business of selling safes.

Yukiko had completed the compulsory eight grades of public school and was living at home when a neighbor lady encouraged her to think about going to the United States, as a nice country where she could have a good life. Yukiko began to seriously consider moving someday to America.

The neighbor knew C.M. Furuta very well. He was born in 1882 in a rural area of the Hiroshima Prefecture, about 40 kilometers from the city, where his land-poor family farmed. After his father died when Furuta was five years old, his older brother decided to immigrate to Hawaii. His persistent suggestions led Furuta to leave for America.

RIGHT: Japanese agricultural workers in Hawaii, circa 1900.

In 1900, Furuta set sail for Hawaii. But when the boat arrived, passengers were informed that because a contagion was spreading throughout the islands, they would not be allowed to disembark in Hawaii. Instead of Hawaii, Furuta came to the United States mainland, disembarking in Tacoma, Washington. He secured employment at a sawmill at first.

Following some railroad work in the Tacoma area, Furuta--who had heard about Orange County good weather and job prospects in the celery fields of Wintersburg and Smeltzer--decided to move there (circa 1904).

Yukiko, though, had never met or even heard about Furuta until one day in 1912. The neighbor woman who had championed America invited her to a public bath house. There she told Yukiko, "Go home before me and if some guests come to your house, please serve them an ashtray and cigarette set." Without suspecting anything, Yukiko duly followed her neighbor's directive. Soon after her arrival, two male guests--C.M. Furuta and a baishakunin (go between)--appeared.

Clearly, this was a prelude to an arranged marriage, which occurred on October 15, 1912, in a civil ceremony at the baishakunin's home. The Yajimas obviously knew about and approved of the fact that Furuta, then in his twelfth year in the United States, had saved enough money to buy his Wintersburg acreage and was planning to build a house on it for his new bride.

ABOVE: The congregation of the Wintersburg Japanese Presbyterian Mission in front of the Mission building circa 1911, just prior to the Furuta's marriage. (Photo courtesy of Wintersburg Presbyterian Church) © ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

While living with the Yajima family for two months after the wedding, Furuta shared with his wife some information about his experience in the U.S. He told her that he and four other men had started their own celery farm on leased land located on what is now Goldenwest Street. The farm failed, probably because the partners did not know how to manage it. They did succeed, however, in running up a large debt. Because Furuta's partners had run away to escape repaying the debt, he was left with the responsibility.

Yukiko found out how Furuta ultimately discharged the debt. Reverend Terasawa had baptized Furuta a Christian--the first person of Japanese ancestry to be baptized in Orange County. Terasawa took care of Furuta, treating him like his son. Furuta regarded Terasawa as his father and learned English from him. In the evenings, Furuta would commute to the Wintersburg Mission by bicycle, and was a sincere Christan, and an honest, hard-working man who did not drink or smoke.

Furuta developed a very good reputation from the hakujin (Caucasian) farm owner from whom he and his partners had rented the land. The owner so trusted Furuta, he loaned him money. Furuta worked hard to not only repay his debt to the owner, but also raise sufficient money to purchase land in Wintersburg along with Reverend Terasawa.

LEFT: The opening of the San Francisco municipal railway in December 1912, at the time of Yukiko Furuta's arrival in America.

On Dec. 6, 1912, the Furutas sailed from Yokohama, Japan to the U.S. After about fifteen days at sea, they arrived in San Francisco. There they spent a week--including New Year's--as house guests of the Terasawas. Mrs. Terasawa took the kimono-clad Yukiko shopping at Market Street to buy her first Western dress for her life in America.

The Furutas then traveled from San Francisco to Los Angeles, staying at a hotel in Little Tokyo. While Yukiko remained at the hotel, C.M. Furuta commuted by streetcar to Orange County, disembarking at the Huntington Beach station and using a bicycle or buggy to get to Wintersburg. There he made preparations for the construction of their home. First, he had to borrow money from a Huntington Beach bank, which extended him a loan because he had land as equity. He then arranged for a Caucasian carpenter to build the house.

RIGHT: The Pacific Electric Railway ("red car") in Little Tokyo, circa 1918, which connected to a station in Huntington Beach. After moving to Wintersburg, Yukiko Furuta took the red car to Little Tokyo now and then for shopping.

Although the house was small--a living room, kitchen and two bedrooms--it was considered very nice for a Nihonjin (Japanese) in the Wintersburg area. There was no electricity or gas, the bathroom was an outhouse, while the front of the house was so muddy when it rained it made walking nearly impossible. Still, "at the time," recalled Yukiko in her interview, their house "was very remarkable and everyone else admired it very much, because other Japanese who owned houses bought old houses."

In Wintersburg, only two other Nikkei families besides the Furutas then owned houses: the Asaris and the Terehatas. The Terehata house was on part of the Furuta property and was an old house relocated from another site to Wintersburg. The Asari house was near the Asari store, on the north side of present day Warner Avenue and east of the railroad tracks (close to what is now Lyndon Street).

Yukiko stayed in Los Angeles until the home was nearly completed. By the time Yukiko came to live in Wintersburg, the nearby market had been sold by T. M. Asari to one of his former delivery boys, Gunjiro Tajima. Like the Furutas, Tajima immigrated to the U.S. from Hiroshima.

The Tajima market in Wintersburg was divided by a wall, with half of it a barbershop run by an Issei man. There also was a pool hall, which Yukiko remembered being frequented by Wintersburg's Mexican Americans who lived east of the railroad tracks on the north side of Wintersburg (Warner) Avenue across from the Furuta's property.

LEFT: A circa 1960s topographic map shows the location of the Southern Pacific Railroad line through Wintersburg, the former Cole ranch on the southwest corner of Wintersburg (Warner) and Gothard, and the Warner Avenue Drive-In in the location of the former armory where Wintersburg residents met in 1904 to discuss building churches. The Furuta property is at the southeast corner of Wintersburg Avenue and Nichols Lane.

Tajima's market was fairly big and carried groceries and clothing. All of the Japanese people living in the rural Wintersburg-Smeltzer-Talbert area shopped there. While the Furutas lived close, this was not the case for many of the other Issei shoppers. The market employed delivery boys to reach customers throughout the surrounding countryside.

The Furutas only neighbor was the Nichols family (editor's note: in the vicinity of present-day Nichols Lane). Otherwise, the Furutas lived in near isolation. This was especially true for Yukiko, since she stayed in her home almost all the time while her husband left daily for work. Because of the anti-Japanese feeling pervasive in Orange County at that time--coupled with Yukiko's lack of English--C.M. Furuta cautioned her to be sure to keep the door of the house locked.

C.M. Furuta's daily work was cultivating celery, sugar beets, and beans on land he leased from M.C. Cole in partnership with Henry Akiyama. After living in their bungalow, the Furutas in 1913 rented it to a Mexican American family and moved to a large two-story home on the Cole ranch. Since the house was so big, the Furutas made their home on the bottom floor and invited Akiyama to live on the top floor. Akiyama was still single then, and Yukiko agreed to cook all of his meals as well as those for her husband and herself. Unfortunately, their joint farming venture did not prosper and within a year they incurred a staggering $10,000 debt.

ABOVE: Yukiko Furuta with her son, Raymond, feeding chickens at the Cole ranch, circa 1915. The Cole ranch was located on the site of present-day Ocean View High School off Gothard Avenue. (Photo courtesy of Center for Oral and Public History, California State University Fullerton, PJA 310) © ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

Akiyama happened to see a photograph of Yukiko's younger sister, Masuko Yajima, and intimated he might want to marry her. Knowing her family in Japan was not doing well economically and feeling that it would be nice to be joined by her sister, Yukiko encouraged the marriage. She wrote to her father, who responded that Yukiko must be lonely in Orange County and that it would be a good idea for Masuko to join her by marrying Akiyama. In the fall of 1915, Masuko sailed to San Francisco to meet Akiyama. On Nov. 11, 1915, after being married by Reverend Teresawa, they went by train to Orange County, making their home at the Cole ranch with the Furutas.

C.M. Furuta's and Henry Akiyama's partnership lasted until 1915. With some timely advise from H. Larta--who farmed the land adjacent to theirs and was a member of the mother Presbyterian church for the Wintersburg Mission--they began to grow potatoes and corn, instead of celery and sugar beets, alongside their bean crop. By the time World War I broke out in 1914, the cost of food rose steeply and the prices for agricultural products rose. Furuta and Akiyama had a bumper harvest that year and the next. They netted enough profit to extinguish their total debt.

RIGHT: Sugar beet fields in Huntington Beach from an early postcard, circa 1915.

Yukiko recalled M.C. Cole's son, a carpenter, may have become jealous of the large profit being made farming his family's land. With their lease coming to an end in 1915, the son--noting that Furuta had built a house on his own land--said, "Why don't you go to your own house and live there?" Akiyama stayed on at the Cole ranch, while the Furutas moved back to their property, along with their son, Raymond, born in 1914. They expanded their house with an indoor bathroom and additional rooms to accommodate the arrival of more children.

Perhaps three or four years after the Furutas moved back to their home, Akiyama grew tired of farming. C.M. Furuta invited him to live in the home previously occupied by the Terehatas. Akiyama then leased land from T.M. Asari to farm and worked part time at a nearby hakujin-owned nursery, while growing goldfish in a small pond.

Whereas Akiyama's farming was unsuccessful, his goldfish venture turned out well. He built a bigger pond and launched his goldfish business, which in time would make him one of the wealthiest Japanese Americans in pre-WWII Orange County.

Meanwhile, Furuta cobbled together an income from growing strawberries on his own land, helping Issei Kyutaro Ishii--a Wintersburg Japanese Presbyterian Mission congregant and father of Charles Ishii--farm asparagus, as well as working horses for other Wintersburg farmers. In 1927, when Akiyama bought forty acres for a new goldfish business in Westminster, Furuta took over his goldfish pond on the Furuta property.

Reverend Kenji Kikuchi: The Wintersburg Japanese Presbyterian Mission and Church

The interview with Reverend Kenji Kikuchi extends the Wintersburg story from the Issei generation to the Nisei generation. By the time of his arrival in 1926, there were about fifty Issei farmers in the area. Most of them--like Furuta and Akiyama--had gotten married, either through an arranged marriage or the "picture bride" system, had started families, and developed family farms.

Before immigrating to America in 1924 from the village of Watari in the Miyagi Prefecture, Kikuchi had been raised in a farm family as a practicing Shintoist and Buddhist. In Watari, he was influenced by his future father-in-law, Mr. Iwama, a devoted Christian. He not only sent his daughters (including Rev. Kikuchi's future wife, Yukiko Iwama) to a Christian school, but also opened his house for Christian meetings. He invited missionaries to come speak at his own expense.

Rev. Kikuchi attended both a Christian college and seminary in Japan, and then determined to leave for America to further his education at Princeton University in New Jersey.

LEFT: Reverend Kenji Kikuchi and his wife, Yukiko, spent ten years with the Wintersburg Japanese Presbyterian Mission. He helped with the building of the 1934 church building during the Great Depression. (Photo courtesy of Wintersburg Church) © ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

After landing in San Francisco, Kikuchi spent a summer picking strawberries in California's Imperial Valley. He became acquainted with both Issei "blanket carriers" as well as students, like himself, earning money to finance their college education. While in the Imperial Valley, Rev. Kikuchi attended services at the Methodist Church in Brawley. There, he was impressed by the pioneer minister from Japan.

Following this experience, Kikuchi attended the San Francisco Theological Seminary in San Anselmo, a Presbyterian-run insitution. At seminary, Kikuchi prepared for American life while sharpening his English skills.

Next, Kikuchi spent a year at Princeton, where he and two other seminarians were the first Japanese students at the Princeton seminary. They boarded together in the same student club where they also took their meals. Because they longed for Asian cuisine--particularly the taste of soy sauce--they would periodically travel by streetcar to a Chinatown in Trenton, or by train to Philadelphia or New York for Chinese food.

After Princeton, Kikuchi returned by train to California as a summertime student pastor for a small Japanese church in Sacramento, living in the parsonage. In addition to becoming familiar with the Japanese settlement in Sacramento, Kikuchi traveled to the San Joaquin and Sacramento valleys viewing different types of Japanese communities and churches.

A minister friend in Long Beach wrote to Kikuchi that the church in Wintersburg, though quite small, had an opening for a pastor. In Orange County, he was told, most of the Issei were vegetable farmers and many of them raised chili peppers. Without even visiting Orange County, recalled Kikuchi in his interview, "I just followed my intuition that this was the place God gave me to work at."

ABOVE: Sunday school at the Wintersburg Japanese Presbyterian Mission, circa 1924, prior to Reverend Kikuchi's arrival in Wintersburg. (Photo courtesy of Wintersburg Church) © ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

What he first noticed about the Wintersburg Mission was that the corner lot was overgrown with dry weeds. This neglect had occurred because his pedecessor, Reverend Junzo Nakamura, had left Orange County some months previously for a San Diego Japanese church whose congregation included a large number of former Smeltzer farmers.

Kikuchi focused his attention on his congregation, "then about a hundred Japanese people, Issei and Nisei, came to the area, so I was deeply determined to take care of them. It was a strong impression I received. So for ten years, I never got tired, never became disappointed, and thoroughly enjoyed myself; (and I believe) most of the people enjoyed our lives with us like we were a family."

During his decade of service to the Wintersburg Japanese Presbyterian Church, Kikuchi pursued a "practical mission." In his sermons delivered in Japanese (Sunday school classes for the Nisei were conducted in English), he talked about practical application of Christian principles to the daily lives of farmers and their families.

A typical sermon, Kikuchi explained in his interview, "might be about father-son relations or neighbor relations, something like that. And it was also about how to act when you met some difficulty in life such as sickness."

ABOVE: The Wintersburg Japanese Presbyterian Mission and manse off Wintersburg (Warner) Avenue, circa 1912 - 1915. Note the stand of gum trees in the background which were used for firewood. (Photo courtesy of Wintersburg Church) © ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

When asked if he provided the church members with legal advice, Kikuchi responded: "Just everyday living advice. The people came to see the minister in case of sickness, some school matter, or family matters. How to help them was the meaning of the Church's existence as well as the minister's. I felt that I had to help the people even when I was busy. To serve them and help them socially was the minister's mission in church work."

As to whether his parishioners were moved by religious or social considerations, Kikuchi was of the opinion that at first it was social, but eventually it was Christian teaching, doctrines, and faith. "Some people understood the Christian way quickly and some stuck to the old Japanese tradition." He felt that especially the young people, the Nisei mostly from Buddhist families, reacted favorably to Christianity and proved very cooperative as community and church members.

Kikuchi was paid $70 per month, which included his housing in the adjacent manse off Wintersburg Avenue. The Presbyterian Conference of Los Angeles provided $25, the mother church paid $17, and the rest of his salary came through offerings from the local Japanese community. In addition, many Issei farmers donated crates of vegetables to the Kikuchi family, which grew to include five children.

Also, parishioners would volunteer their labor to make repairs on the Church and manse. Often, the person doing the repairs was neighbor C.M. Furuta.

RIGHT: Huntington Beach's present-day Pacific Coast Highway at Main Street and the Pier, circa 1930s. (Photo courtesy of Orange County Archives)

By 1930, the Wintersburg Japanese Presbyterian Church congregation had grown to the point where a new building was needed. Raising money for the new church building was especially daunting due to the Great Depression. There was a designated church committee assigned the responsibility of raising funds, but practically everyone in the congregation worked as fundraisers. Little by little, donations accumulated.

"First," recalled Kikuchi, "we deposited money in the Huntington Beach Bank, a state bank. But in the prime of the Depression, the deposits were frozen. Charlie Ishii's father and I ran to (the bank) but the bank was closed. We almost felt like crying. But, later, when we fixed pews in the church, we could draw our deposit from the bank after the arrangement by the government."

Finally in 1934, a new church building (adjacent to the original Mission and manse) was dedicated as the Wintersburg Japanese Presbyterian Church. Whereas the Mission, erected by 1910, measured approximately 50 feet north-south by 20 feet east-west, the 1934 Church building measured 30 feet north-south by 82 feet east-west.

As its first minister, Kikuchi served Wintersburg parishioners until 1936. Thirty years later, the congregation moved in 1966 to its new church building in Garden Grove (now part of Santa Ana), where it remains today.

ABOVE: A postcard image of the Wintersburg Japanese Presbyterian Church, circa 1934, commemorating the new chapel and the mission founding in 1904. (Photo courtesy of Wintersburg Church) © ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

All rights reserved.

No part of the Historic Wintersburg blog may be reproduced or duplicated

without prior written permission from the author and publisher, M. Adams

Urashima.

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)