A holiday message from the Pacific Goldfish Farm from the Huntington Beach News of sixty years ago. (Image, Huntington Beach News, December 24, 1953; special thanks to Chris Jepsen, Orange County Archives, for finding this!)

Henry Kiyomi Akiyama--the brother-in-law of Charles Mitsuji Furuta--started experimenting with Charles on the first goldfish pond on the Furuta farm, then at the Cole Ranch in Wintersburg Village. Eventually, Akiyama would go on to own the "world's largest goldfish farm"--forty acres of goldfish ponds located at the site of today's Westminster Mall, in Westminster, California (adjacent to Huntington Beach).

The address noted on the advertisement is just north of Bolsa Avenue, near the 405 Freeway. The construction of the freeway prompted the City of Westminster to acquire the property for commercial development.

The Pacific Goldfish Farm can be seen in this 1955 photograph, north of Bolsa Avenue and west of Golden West. From the aerial view, there appear to be approximately 100 ponds, in which Akiyama bred goldfish and koi. The buildings contained an indoor hatchery. (Photograph courtesy of the Orange County Archives)

We wish all our readers and friends of the Historic Wintersburg preservation effort a very happy holiday season! We continue in 2014 our work to preserve the rare Japanese pioneer farm and mission property that shared in the early 1900s settlement and development of Huntington Beach. We'll have some exciting new ways to share the history of Historic Wintersburg in 2014!

© All rights reserved.

No part of the Historic Wintersburg blog may be reproduced or duplicated

without prior written permission from the author and publisher, M. Adams

Urashima.

Saturday, December 21, 2013

Thursday, November 21, 2013

The Japanese Mission Trail: California's lost and at-risk history along the Pacific Coast

LEFT: Dr. Ernest Adolphus Sturge, arriving in Yokohama circa 1910 - 1915, was honored in 1904 with the Order of the Rising Sun by Emperor Meiji for his work establishing Japanese missions along the West Coast for the Presbyterian Church. Sturge took on the stewardship of Japanese missions in 1886, and was present at the opening ceremony for the Wintersburg Japanese Presbyterian Mission in 1910. He had a close relationship with the Wintersburg Mission's first clergy, Rev. Joseph K. Inazawa. (Photograph, Bain News Service, Library of Congress)

~Updated September 2017~

The California State Parks describes the California Missions Trail importance as "humble, thatch-roofed beginnings to the stately adobes we see today, the missions represent a dynamic chapter of California's past. By the time the last mission was built in 1823, the Golden State had grown from an untamed wilderness to a thriving agricultural frontier on the verge of American statehood."

LEFT: The San Juan Capistrano Mission in Orange County, circa 1910. (Photograph, Library of Congress)

The history represented by the Spanish missions trail is of European settlement, but it is not the only mission trail in California. There is a missing chapter, pages torn out and forgotten, as the State transitioned from an agricultural frontier toward the social change and urban development of the 20th Century.

In 1885, the first Japanese mission in California marked the beginning of an effort for a new group of pioneers to establish communities as they assimilated to American life. It is integral to the dawning of Pacific Rim interaction and migration.

While the twenty-one Spanish Franciscan missions were stationed approximately 30 miles apart---a day or two ride by horseback---the Japanese missions sprang up in communities where immigrants established themselves for work. In Orange County, work in the early 1900s focused in the celery and chili pepper fields surrounding the Wintersburg Village, before gradually moving south and east.

.jpg) In contrast to the Spanish missions, there was no effort to create a labor force from Native Californians or other populations; in this case, the missions were established by the those already laboring in the fields. And, unlike the Spanish missions, the Japanese missions were not representative of a dominant, conquering culture.

In contrast to the Spanish missions, there was no effort to create a labor force from Native Californians or other populations; in this case, the missions were established by the those already laboring in the fields. And, unlike the Spanish missions, the Japanese missions were not representative of a dominant, conquering culture.

RIGHT: The Wintersburg Japanese Presbyterian Mission, circa 1911-1912. (Photograph courtesy of Wintersburg Presbyterian Church) ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. ©

These were the missions of those who faced exclusion, discrimination and a succession of laws that prevented citizenship and land ownership. These were the missions that followed their communities into the forced evacuation and confinement of World War II, safeguarding their congregants' belongings and providing comfort for those inside relocation camps. These were the missions whose clergy were incarcerated along with their congregations. These were the missions who helped their flock return to West Coast communities after World War II, providing both shelter and guidance as they rebuilt lives.

The surviving Japanese mission sites are representative of those subjected to the largest forced evacuation and confinement in American history. They witnessed an often intense and painful struggle for civil liberties and citizenship in America, and were instrumental in the remarkable post-World War II recovery of Japanese Americans.

ABOVE: A cenotaph for Dr. E.A. Sturge in the Japanese Cemetery in Colma, California, notes "he gave us his very homes for our use in San Francisco and San Mateo." Sturge helped establish fourteen Japanese Presbyterian missions on the Pacific Coast.

In loving memory of Dr. E. A. Sturge

Physican, author, artist, and poet

Spiritual father to us

He loved the Japanese

For forty eight years onward from 1886 he dedicated his life to us

He established fourteen Japanese Presbyterian churches on the Pacific coast

~Cenotaph for Dr. E.A. Sturge, Japanese Cemetery, Colma, California

Ernest Adolphus Sturge, M.D., Ph.D.

In San Francisco, the Christ United Presbyterian Church remembers E.A. Sturge each year on his birthday, referred to as "Sturge Sunday." The mission was organized in San Francisco on May 16, 1885 as the First Japanese Presbyterian Church in San Francisco. It is the oldest Japanese Christian church in America.

ABOVE: Ernest Adolphus Sturge and his wife with a group of mission assistants in northern California. (Image, The Spirit of Japan, 1903)

The year after its organization, Sturge was appointed by the national Presbyterian Church in 1886 to serve as Missionary of the Presbyterian Board to the Japanese in California, developing a statewide mission plan. His biography notes the Sturges "cheerfully taught classes of Japanese students who were anxious to learn the English language." The couple is acknowledged as among the first to initiate mission efforts in the Japanese immigrant community in America.

RIGHT: Mrs. C.H. Sturge, wife of Ernest Adolphus Sturge and his partner in the Japanese mission efforts. (Image from The Spirit of Japan, 1903)

Sturge was not an ordained minister, but held two doctorates: one as an M.D. and the other a Ph.D. He had traveled through Asia, working as a medical missionary in Siam (Thailand) and in China.

His time in Japan and with the Japanese community in America---originating in San Francisco---became the catalyst for his life's work.

Henry Collin Minton, a chair at the San Francisco Theological Seminary from which graduated some of the first Japanese clergy, wrote "there is no more interesting missionary work on this continent than that which has been quietly but efficiently carried on all these years among the Japanese community" (in California).

In 1903, Sturge was honored by the publication of a book entitled, The Spirit of Japan, which included a selection of essays from colleagues and poetry by Sturge. It was published by the Japanese Young Men's Christian Association as a surprise to recognize his "indefatigable zeal and painstaking kindness"and in "recognition for the years of ernest toil for the education and advancement of the Japanese."

LEFT: Ernest Adolphus Sturge, M.D., Ph.D. (Image from The Spirit of Japan, 1903)

One of The Spirit of Japan authors and editors, Reverend Joseph K. Inazawa submitted the volume to the Library of Congress, and it was entered officially by an Act of Congress in 1903.

Rev. Inazawa was the first clergy at the Wintersburg Japanese Presbyterian Mission in 1910. He and his wife, Kate Alice Goodman, were the first to live in the manse at Historic Wintersburg.

Inazawa writes of Sturge in The Spirit of Japan, "our beloved doctor has been my esteemed guardian, admirable teacher, confidential friend and elder brother..."

RIGHT: Reverend Joseph K. Inazawa, the first clergy officially assigned to the Wintersburg Japanese Presbyterian Mission as the first mission building opened in 1910. (Photograph courtesy of Wintersburg Presbyterian Church) All rights reserved. ©

Another entry in the book is from Kisaburo Uyeno, His Imperial Japanese Majesty's Consul in San Francisco, who noted by then Sturge had been living and working with the Japanese in America for twenty years.

"Since the opening of friendly relations with America, our people have been immigrating into this vast and wonderful country; and we are, today, nearly 20,000 strong. Many of our pioneers have encountered great difficulties and perplexities," writes Uyeno. "Some have left behind them only their graves to narrate the tale of their careers, and all have come with the feeling that they were among 'a strange people and under strange stars.' "

ABOVE: Portraits of those involved in California's Japanese mission effort, including Dr. E.A. Sturge (#1) and Wintersburg Japanese Presbyterian Mission clergy, Reverend Joseph K. Inazawa (#5). (Image from The Spirit of Japan, 1903)

"But as we often see beautiful flowers blooming here and there among the briers and dried thorns, so these people have found on this stranger soil many kind hearts and great souls, who have shown them consideration and sympathy," continues Uyeno. "For them we are greatly indebted for our prosperity on this coast and our friendship with the people here. Among these kindly Americans, Dr. Sturge stands very prominent."

Writing from Tokyo, Japan, Reverend Fumio Matsunaga says of Sturge that "though an American gentleman he resembles a Japanese knight of medieval age." The admiration was mutual. Rev. Matusnaga had once presented Sturge with a copy of Bushido, The Soul of Japan by Dr. Inazo Nitobe, and recalled how Sturge was taken by the explanation of the Japanese code of honor.

Published in 1903, The Spirit of Japan debuted one year before the founding of the Wintersburg Mission in 1904. At the time of publication, there were four Japanese Presbyterian missions in California: San Francisco, Watsonville, Salinas and Los Angeles.

The next year, the Wintersburg Mission was founded with the help of Reverend Hisayoshi Terasawa, who had traveled down from San Francisco---where Sturge was living---to work with Presbyterian and Methodist missionaries. He began holding services in a barn in Wintersburg Village.

LEFT: Two of the four California Japanese missions established as of 1903---one in Watsonville and the other in Los Angeles---are shown in The Spirit of Japan, published one year before the fifth mission, the Wintersburg Mission, was founded in 1904. The other missions at that time were in San Francisco and Salinas, California. (Image, The Spirit of Japan)

Charles Furuta was among Rev. Terasawa's first congregants, the first Japanese baptized Christian in Orange County, and became a trustee and elder of the Mission. His donation of land in Wintersburg Village fostered the Mission's growth into an official church in 1930 and allowed for the second, larger church building in 1934. This places Charles Furuta among those pioneers who helped establish and support the Japanese mission trail in California.

Wintersburg Village

By 1902, seventeen years after the first Japanese Presbyterian Mission was established in northern California, the Presbyterian and Methodist Evangelical churches in nearby Westminster had taken note of Orange County's growing Japanese community. Rev. Inazawa was sent to investigate. By 1904, Rev. Inazawa and Rev. John Junzo Nakamura met with Rev. Terasawa, leading to the founding of the Wintersburg Mission.

At that time, there was no Presbytery established in Orange County. The Los Angeles Presbytery had no funds, leaving the Wintersburg Mission support to the local community. In an interfaith effort, nearby Presbyterian and Methodist congregations contributed, as did the Christian Endeavor Union of Orange County. Donations for the first chapel came from the surrounding farmland, including from some of Huntington Beach's and Westminster's prominent pioneer families.

Rev. Nakamura stayed on to oversee the building of the Mission and manse, with "the aid of our countrymen and some good American friends."

ABOVE: The opening of the Mission on May 8, 1910, with the manse to the left and in the background, the Terahata home that had been moved temporarily to the property. At the center of the crowd along then-country road Wintersburg Avenue can be seen Charles Furuta, on whose land the Mission stood, and Dr. E. A. Sturge. (Photograph courtesy of Wintersburg Presbyterian Church) ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. ©

Sturge attended the opening ceremony of the Wintersburg Mission on May 8, 1910, to see the work of his protégé, Rev. Inazawa, as did Rev. H.C. Cockrum of Westminster and five other local clergy. It was a large gathering for the little Wintersburg Village.

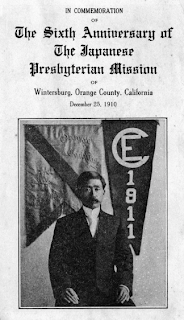

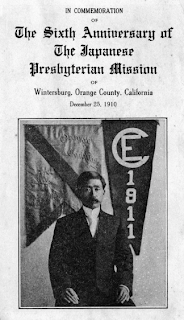

In a December 25, 1910, pamphlet marking the sixth anniversary of the Mission's founding, Rev. Nakamura describes how he made the circuit in rural Orange County, a trip that today would take a day took a week to complete.

LEFT: Japanese farmers on horseback at Irvine Ranch, Orange County, circa 1920. (Photograph snip courtesy of California State University Fullerton, Center for Oral and Public History PJA 497) ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. ©

"Last summer, I tried a fortnight's campaign of gospel preaching, during which I traveled over two-hundred and twenty-five miles, visited forty families and camps, preached to four-hundred and fifty souls, distributed three-hundred and sixty copies of the Gospel of Matthew and sold eighteen copies of the New Testament," writes Rev. Nakamura, who adds that he converted four souls.

Rev. Nakamura would have traveled by horseback through the farm fields, ranches and open land to reach the scattered Japanese immigrants, riding through the tules of the peatlands. His account also makes note of the annual Christian convention held in Huntington Beach in 1910, at which his group received the Orange County Christian Endeavor Union banner.

Rev. Nakamura would have traveled by horseback through the farm fields, ranches and open land to reach the scattered Japanese immigrants, riding through the tules of the peatlands. His account also makes note of the annual Christian convention held in Huntington Beach in 1910, at which his group received the Orange County Christian Endeavor Union banner.

"It was entirely unexpected!" writes Rev. Nakamura, who adds that they shared a Thanksgiving meal with"a few American friends" in Orange County afterward. Although noting that "at present our Mission has no permanent resources," he is encouraged they started with "fifteen active members, five associate members, and fifteen friends."

RIGHT: Reverend John Junzo Nakamura with the Young Christian Endeavor Union banner. (Image courtesy of the Furuta family) ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. ©

Rev. Nakamura describes the mission field as including Wintersburg, Bolsa Beach, Smeltzer, Bolsa, Garden Grove, Old Newport, Talbert and Huntington Beach. In 1910, he estimated there were about 300 Japanese permanently living in the area.

Japanese Missions in California

The Presbyterian Japanese Mission trail in California is joined by the early Methodist Evangelical, Episcopalian, congregational Japanese missions and Japanese Buddhist temples established during the pioneer settlement period starting in the late 1800s. Most were established through interfaith efforts, community helping community. Not all have survived the politics and development of California.

As the United States entered World War I in 1917---and after 30 years working to establish Japanese missions in California---Sturge provided an update as part of the Annual Report of the Board of Foreign Missions to the national Presbyterian Church.

"About 90% of the 100,000 Japanese in the U.S. are on the Pacific Coast...there are 66 churches and missions belong to twelve denominations," writes Sturge. "The work among the Japanese on the coast is carried on at San Francisco, Salinas, Watsonville, Los Angeles, Wintersburg, Hanford, Stockton, Sacramento, Monterey, Long Beach. There are 17 unorganized churches or groups and five organized churches..."

LEFT: Viscount Kikujiro Ishii, second from left, visited the United States in 1917 on a special mission for the Imperial government of Japan. Despite California's passage of the Alien Land Law of 1913 and restrictions on immigration, Japan and the U.S. federal government worked to maintain relations on the Pacific Rim. (Photograph, Library of Congress)

This also was the year Viscount Kikujiro Ishii visited the United States on behalf of Japan, as part of a special mission to assure good relations with the United States. He stopped in San Francisco on his way to Washington, D.C., to meet with and address Californians, remarking on the hospitality he had been shown:

In response, California attorney Gavin McNab---who acted as toastmaster for the official state visit and was a member of President Woodrow Wilson's industrial council---invoked the romance of California's Franciscan missions, perhaps not realizing another California mission trail had taken root three decades earlier.

Mapping the Missions

Today, there is a need to put the Japanese mission trail on the map before it is lost to time. Historical missions like the Wintersburg Japanese Mission have been demolished or are in jeopardy. The Wintersburg Japanese Mission---the oldest Japanese mission in most of Southern California---is at risk of being lost forever, as are all six historic buildings at Historic Wintersburg, including the Furuta Gold Fish Farm. We invite our readers to send in the known locations and historical photos of California's Japanese Mission Trail.

ABOVE: Part of the Wintersburg Village community gathering for the dedication of the second church building at Historic Wintersburg, the 1934 Depression-era Church. The occasion also marked the 30th anniversary of the Mission's founding. The diverse crowd represents the support the Mission effort received from the surrounding countryside. (Photograph courtesy of Wintersburg Presbyterian Church) ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. ©

ENDANGERED: The Huntington Beach City Council voted 4-3 on November 4, 2013, to certify the Environmental Impact Report which approves the zone change of Historic Wintersburg from residential to commercial / industrial, and approves the demolition of all six historic structures.

In 2014, Historic Wintersburg was named one of America's 11 Most Endangered Historic Places. In 2015, Historic Wintersburg was named a National Treasure. The property has been noted by the National Park Service as potentially eligible for the National Register of Historic Places under Criteria A, Japanese American Settlement of the American West.

As of September 2017, Historic Wintersburg--owned by Republic Services--remains endangered.

SUPPORT PRESERVATION: Join our Facebook page at https://www.facebook.com/pages/Historic-Wintersburg-Preservation-Task-Force/433990979985360

© All rights reserved. No part of the Historic Wintersburg blog may be reproduced or duplicated without prior written permission from the author and publisher, M. Adams Urashima.

~Updated September 2017~

The California State Parks describes the California Missions Trail importance as "humble, thatch-roofed beginnings to the stately adobes we see today, the missions represent a dynamic chapter of California's past. By the time the last mission was built in 1823, the Golden State had grown from an untamed wilderness to a thriving agricultural frontier on the verge of American statehood."

LEFT: The San Juan Capistrano Mission in Orange County, circa 1910. (Photograph, Library of Congress)

The history represented by the Spanish missions trail is of European settlement, but it is not the only mission trail in California. There is a missing chapter, pages torn out and forgotten, as the State transitioned from an agricultural frontier toward the social change and urban development of the 20th Century.

In 1885, the first Japanese mission in California marked the beginning of an effort for a new group of pioneers to establish communities as they assimilated to American life. It is integral to the dawning of Pacific Rim interaction and migration.

While the twenty-one Spanish Franciscan missions were stationed approximately 30 miles apart---a day or two ride by horseback---the Japanese missions sprang up in communities where immigrants established themselves for work. In Orange County, work in the early 1900s focused in the celery and chili pepper fields surrounding the Wintersburg Village, before gradually moving south and east.

.jpg) In contrast to the Spanish missions, there was no effort to create a labor force from Native Californians or other populations; in this case, the missions were established by the those already laboring in the fields. And, unlike the Spanish missions, the Japanese missions were not representative of a dominant, conquering culture.

In contrast to the Spanish missions, there was no effort to create a labor force from Native Californians or other populations; in this case, the missions were established by the those already laboring in the fields. And, unlike the Spanish missions, the Japanese missions were not representative of a dominant, conquering culture. RIGHT: The Wintersburg Japanese Presbyterian Mission, circa 1911-1912. (Photograph courtesy of Wintersburg Presbyterian Church) ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. ©

These were the missions of those who faced exclusion, discrimination and a succession of laws that prevented citizenship and land ownership. These were the missions that followed their communities into the forced evacuation and confinement of World War II, safeguarding their congregants' belongings and providing comfort for those inside relocation camps. These were the missions whose clergy were incarcerated along with their congregations. These were the missions who helped their flock return to West Coast communities after World War II, providing both shelter and guidance as they rebuilt lives.

The surviving Japanese mission sites are representative of those subjected to the largest forced evacuation and confinement in American history. They witnessed an often intense and painful struggle for civil liberties and citizenship in America, and were instrumental in the remarkable post-World War II recovery of Japanese Americans.

ABOVE: A cenotaph for Dr. E.A. Sturge in the Japanese Cemetery in Colma, California, notes "he gave us his very homes for our use in San Francisco and San Mateo." Sturge helped establish fourteen Japanese Presbyterian missions on the Pacific Coast.

In loving memory of Dr. E. A. Sturge

Physican, author, artist, and poet

Spiritual father to us

He loved the Japanese

For forty eight years onward from 1886 he dedicated his life to us

He established fourteen Japanese Presbyterian churches on the Pacific coast

~Cenotaph for Dr. E.A. Sturge, Japanese Cemetery, Colma, California

Ernest Adolphus Sturge, M.D., Ph.D.

In San Francisco, the Christ United Presbyterian Church remembers E.A. Sturge each year on his birthday, referred to as "Sturge Sunday." The mission was organized in San Francisco on May 16, 1885 as the First Japanese Presbyterian Church in San Francisco. It is the oldest Japanese Christian church in America.

ABOVE: Ernest Adolphus Sturge and his wife with a group of mission assistants in northern California. (Image, The Spirit of Japan, 1903)

The year after its organization, Sturge was appointed by the national Presbyterian Church in 1886 to serve as Missionary of the Presbyterian Board to the Japanese in California, developing a statewide mission plan. His biography notes the Sturges "cheerfully taught classes of Japanese students who were anxious to learn the English language." The couple is acknowledged as among the first to initiate mission efforts in the Japanese immigrant community in America.

RIGHT: Mrs. C.H. Sturge, wife of Ernest Adolphus Sturge and his partner in the Japanese mission efforts. (Image from The Spirit of Japan, 1903)

Sturge was not an ordained minister, but held two doctorates: one as an M.D. and the other a Ph.D. He had traveled through Asia, working as a medical missionary in Siam (Thailand) and in China.

His time in Japan and with the Japanese community in America---originating in San Francisco---became the catalyst for his life's work.

Henry Collin Minton, a chair at the San Francisco Theological Seminary from which graduated some of the first Japanese clergy, wrote "there is no more interesting missionary work on this continent than that which has been quietly but efficiently carried on all these years among the Japanese community" (in California).

In 1903, Sturge was honored by the publication of a book entitled, The Spirit of Japan, which included a selection of essays from colleagues and poetry by Sturge. It was published by the Japanese Young Men's Christian Association as a surprise to recognize his "indefatigable zeal and painstaking kindness"and in "recognition for the years of ernest toil for the education and advancement of the Japanese."

LEFT: Ernest Adolphus Sturge, M.D., Ph.D. (Image from The Spirit of Japan, 1903)

One of The Spirit of Japan authors and editors, Reverend Joseph K. Inazawa submitted the volume to the Library of Congress, and it was entered officially by an Act of Congress in 1903.

Rev. Inazawa was the first clergy at the Wintersburg Japanese Presbyterian Mission in 1910. He and his wife, Kate Alice Goodman, were the first to live in the manse at Historic Wintersburg.

Inazawa writes of Sturge in The Spirit of Japan, "our beloved doctor has been my esteemed guardian, admirable teacher, confidential friend and elder brother..."

RIGHT: Reverend Joseph K. Inazawa, the first clergy officially assigned to the Wintersburg Japanese Presbyterian Mission as the first mission building opened in 1910. (Photograph courtesy of Wintersburg Presbyterian Church) All rights reserved. ©

Another entry in the book is from Kisaburo Uyeno, His Imperial Japanese Majesty's Consul in San Francisco, who noted by then Sturge had been living and working with the Japanese in America for twenty years.

"Since the opening of friendly relations with America, our people have been immigrating into this vast and wonderful country; and we are, today, nearly 20,000 strong. Many of our pioneers have encountered great difficulties and perplexities," writes Uyeno. "Some have left behind them only their graves to narrate the tale of their careers, and all have come with the feeling that they were among 'a strange people and under strange stars.' "

ABOVE: Portraits of those involved in California's Japanese mission effort, including Dr. E.A. Sturge (#1) and Wintersburg Japanese Presbyterian Mission clergy, Reverend Joseph K. Inazawa (#5). (Image from The Spirit of Japan, 1903)

"But as we often see beautiful flowers blooming here and there among the briers and dried thorns, so these people have found on this stranger soil many kind hearts and great souls, who have shown them consideration and sympathy," continues Uyeno. "For them we are greatly indebted for our prosperity on this coast and our friendship with the people here. Among these kindly Americans, Dr. Sturge stands very prominent."

Writing from Tokyo, Japan, Reverend Fumio Matsunaga says of Sturge that "though an American gentleman he resembles a Japanese knight of medieval age." The admiration was mutual. Rev. Matusnaga had once presented Sturge with a copy of Bushido, The Soul of Japan by Dr. Inazo Nitobe, and recalled how Sturge was taken by the explanation of the Japanese code of honor.

Published in 1903, The Spirit of Japan debuted one year before the founding of the Wintersburg Mission in 1904. At the time of publication, there were four Japanese Presbyterian missions in California: San Francisco, Watsonville, Salinas and Los Angeles.

The next year, the Wintersburg Mission was founded with the help of Reverend Hisayoshi Terasawa, who had traveled down from San Francisco---where Sturge was living---to work with Presbyterian and Methodist missionaries. He began holding services in a barn in Wintersburg Village.

LEFT: Two of the four California Japanese missions established as of 1903---one in Watsonville and the other in Los Angeles---are shown in The Spirit of Japan, published one year before the fifth mission, the Wintersburg Mission, was founded in 1904. The other missions at that time were in San Francisco and Salinas, California. (Image, The Spirit of Japan)

Charles Furuta was among Rev. Terasawa's first congregants, the first Japanese baptized Christian in Orange County, and became a trustee and elder of the Mission. His donation of land in Wintersburg Village fostered the Mission's growth into an official church in 1930 and allowed for the second, larger church building in 1934. This places Charles Furuta among those pioneers who helped establish and support the Japanese mission trail in California.

Wintersburg Village

By 1902, seventeen years after the first Japanese Presbyterian Mission was established in northern California, the Presbyterian and Methodist Evangelical churches in nearby Westminster had taken note of Orange County's growing Japanese community. Rev. Inazawa was sent to investigate. By 1904, Rev. Inazawa and Rev. John Junzo Nakamura met with Rev. Terasawa, leading to the founding of the Wintersburg Mission.

At that time, there was no Presbytery established in Orange County. The Los Angeles Presbytery had no funds, leaving the Wintersburg Mission support to the local community. In an interfaith effort, nearby Presbyterian and Methodist congregations contributed, as did the Christian Endeavor Union of Orange County. Donations for the first chapel came from the surrounding farmland, including from some of Huntington Beach's and Westminster's prominent pioneer families.

Rev. Nakamura stayed on to oversee the building of the Mission and manse, with "the aid of our countrymen and some good American friends."

ABOVE: The opening of the Mission on May 8, 1910, with the manse to the left and in the background, the Terahata home that had been moved temporarily to the property. At the center of the crowd along then-country road Wintersburg Avenue can be seen Charles Furuta, on whose land the Mission stood, and Dr. E. A. Sturge. (Photograph courtesy of Wintersburg Presbyterian Church) ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. ©

Sturge attended the opening ceremony of the Wintersburg Mission on May 8, 1910, to see the work of his protégé, Rev. Inazawa, as did Rev. H.C. Cockrum of Westminster and five other local clergy. It was a large gathering for the little Wintersburg Village.

In a December 25, 1910, pamphlet marking the sixth anniversary of the Mission's founding, Rev. Nakamura describes how he made the circuit in rural Orange County, a trip that today would take a day took a week to complete.

LEFT: Japanese farmers on horseback at Irvine Ranch, Orange County, circa 1920. (Photograph snip courtesy of California State University Fullerton, Center for Oral and Public History PJA 497) ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. ©

"Last summer, I tried a fortnight's campaign of gospel preaching, during which I traveled over two-hundred and twenty-five miles, visited forty families and camps, preached to four-hundred and fifty souls, distributed three-hundred and sixty copies of the Gospel of Matthew and sold eighteen copies of the New Testament," writes Rev. Nakamura, who adds that he converted four souls.

Rev. Nakamura would have traveled by horseback through the farm fields, ranches and open land to reach the scattered Japanese immigrants, riding through the tules of the peatlands. His account also makes note of the annual Christian convention held in Huntington Beach in 1910, at which his group received the Orange County Christian Endeavor Union banner.

Rev. Nakamura would have traveled by horseback through the farm fields, ranches and open land to reach the scattered Japanese immigrants, riding through the tules of the peatlands. His account also makes note of the annual Christian convention held in Huntington Beach in 1910, at which his group received the Orange County Christian Endeavor Union banner."It was entirely unexpected!" writes Rev. Nakamura, who adds that they shared a Thanksgiving meal with"a few American friends" in Orange County afterward. Although noting that "at present our Mission has no permanent resources," he is encouraged they started with "fifteen active members, five associate members, and fifteen friends."

RIGHT: Reverend John Junzo Nakamura with the Young Christian Endeavor Union banner. (Image courtesy of the Furuta family) ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. ©

Rev. Nakamura describes the mission field as including Wintersburg, Bolsa Beach, Smeltzer, Bolsa, Garden Grove, Old Newport, Talbert and Huntington Beach. In 1910, he estimated there were about 300 Japanese permanently living in the area.

Japanese Missions in California

The Presbyterian Japanese Mission trail in California is joined by the early Methodist Evangelical, Episcopalian, congregational Japanese missions and Japanese Buddhist temples established during the pioneer settlement period starting in the late 1800s. Most were established through interfaith efforts, community helping community. Not all have survived the politics and development of California.

As the United States entered World War I in 1917---and after 30 years working to establish Japanese missions in California---Sturge provided an update as part of the Annual Report of the Board of Foreign Missions to the national Presbyterian Church.

"About 90% of the 100,000 Japanese in the U.S. are on the Pacific Coast...there are 66 churches and missions belong to twelve denominations," writes Sturge. "The work among the Japanese on the coast is carried on at San Francisco, Salinas, Watsonville, Los Angeles, Wintersburg, Hanford, Stockton, Sacramento, Monterey, Long Beach. There are 17 unorganized churches or groups and five organized churches..."

LEFT: Viscount Kikujiro Ishii, second from left, visited the United States in 1917 on a special mission for the Imperial government of Japan. Despite California's passage of the Alien Land Law of 1913 and restrictions on immigration, Japan and the U.S. federal government worked to maintain relations on the Pacific Rim. (Photograph, Library of Congress)

This also was the year Viscount Kikujiro Ishii visited the United States on behalf of Japan, as part of a special mission to assure good relations with the United States. He stopped in San Francisco on his way to Washington, D.C., to meet with and address Californians, remarking on the hospitality he had been shown:

In response, California attorney Gavin McNab---who acted as toastmaster for the official state visit and was a member of President Woodrow Wilson's industrial council---invoked the romance of California's Franciscan missions, perhaps not realizing another California mission trail had taken root three decades earlier.

Mapping the Missions

Today, there is a need to put the Japanese mission trail on the map before it is lost to time. Historical missions like the Wintersburg Japanese Mission have been demolished or are in jeopardy. The Wintersburg Japanese Mission---the oldest Japanese mission in most of Southern California---is at risk of being lost forever, as are all six historic buildings at Historic Wintersburg, including the Furuta Gold Fish Farm. We invite our readers to send in the known locations and historical photos of California's Japanese Mission Trail.

ABOVE: Part of the Wintersburg Village community gathering for the dedication of the second church building at Historic Wintersburg, the 1934 Depression-era Church. The occasion also marked the 30th anniversary of the Mission's founding. The diverse crowd represents the support the Mission effort received from the surrounding countryside. (Photograph courtesy of Wintersburg Presbyterian Church) ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. ©

ENDANGERED: The Huntington Beach City Council voted 4-3 on November 4, 2013, to certify the Environmental Impact Report which approves the zone change of Historic Wintersburg from residential to commercial / industrial, and approves the demolition of all six historic structures.

In 2014, Historic Wintersburg was named one of America's 11 Most Endangered Historic Places. In 2015, Historic Wintersburg was named a National Treasure. The property has been noted by the National Park Service as potentially eligible for the National Register of Historic Places under Criteria A, Japanese American Settlement of the American West.

As of September 2017, Historic Wintersburg--owned by Republic Services--remains endangered.

SUPPORT PRESERVATION: Join our Facebook page at https://www.facebook.com/pages/Historic-Wintersburg-Preservation-Task-Force/433990979985360

© All rights reserved. No part of the Historic Wintersburg blog may be reproduced or duplicated without prior written permission from the author and publisher, M. Adams Urashima.

Tuesday, November 5, 2013

Huntington Beach City Council certifies environmental report, starts demolition clock

CONTEMPLATING THE FUTURE: Yukiko Yajima Furuta, at the Cole Ranch in Wintersburg Village, circa 1914. (Photograph courtesy of the Furuta family). All rights reserved. ©

On November 4, the Huntington Beach City Council voted 4-3 to certify the Environmental Impact Report (EIR) and approve the Statement of Overriding Consideration (which approves the justification for demolition of historic resources), a process under the California Environmental Quality Act (CEQA).

Those voting in support for the re-zoning and demolition action were Mayor Pro Tem Matt Harper, and Council Members Dave Sullivan, Joe Carchio and Jim Katapodis. Those opposing the actions to re-zone and demolish historic structures were Mayor Connie Boardman and Council Members Joe Shaw and Jill Hardy.

The actions approve the re-zoning of the property to commercial / industrial and approve the demolition, although no development plan is proposed. There is a 30-day period after the Notice of Determination for the EIR is filed by the City of Huntington Beach during which another party may file suit.

The City Council added a condition that Rainbow Environmental Services---the waste disposal company that currently owns the property---will provide the Historic Wintersburg Preservation Task Force with an 18-month window to raise funds to relocate the historic structures or, possibly purchase the area of land that includes the historic structures.

Next steps

Our next step will be to prepare the nomination for the National Register of Historic Places, to follow through on the recommendation of the U.S. National Park Service and National Trust for Historic Preservation that the property is potentially eligible for the National Register of Historic Places under Criteria A, Japanese American Settlement of the American West.

And, a major fundraising effort begins. We've only begun and call upon our readers for support. Donations dedicated solely to the preservation of Historic Wintersburg (and with Historic Wintersburg Preservation Task Force and City of Huntington Beach oversight and reporting) can be made via mail or online at http://www.huntingtonbeachca.gov/i_want_to/give/donation-wintersburg.cfm

On November 4, the Huntington Beach City Council voted 4-3 to certify the Environmental Impact Report (EIR) and approve the Statement of Overriding Consideration (which approves the justification for demolition of historic resources), a process under the California Environmental Quality Act (CEQA).

Those voting in support for the re-zoning and demolition action were Mayor Pro Tem Matt Harper, and Council Members Dave Sullivan, Joe Carchio and Jim Katapodis. Those opposing the actions to re-zone and demolish historic structures were Mayor Connie Boardman and Council Members Joe Shaw and Jill Hardy.

The actions approve the re-zoning of the property to commercial / industrial and approve the demolition, although no development plan is proposed. There is a 30-day period after the Notice of Determination for the EIR is filed by the City of Huntington Beach during which another party may file suit.

The City Council added a condition that Rainbow Environmental Services---the waste disposal company that currently owns the property---will provide the Historic Wintersburg Preservation Task Force with an 18-month window to raise funds to relocate the historic structures or, possibly purchase the area of land that includes the historic structures.

Next steps

Our next step will be to prepare the nomination for the National Register of Historic Places, to follow through on the recommendation of the U.S. National Park Service and National Trust for Historic Preservation that the property is potentially eligible for the National Register of Historic Places under Criteria A, Japanese American Settlement of the American West.

And, a major fundraising effort begins. We've only begun and call upon our readers for support. Donations dedicated solely to the preservation of Historic Wintersburg (and with Historic Wintersburg Preservation Task Force and City of Huntington Beach oversight and reporting) can be made via mail or online at http://www.huntingtonbeachca.gov/i_want_to/give/donation-wintersburg.cfm

Friday, October 25, 2013

Decision: Before the City Council on November 4

The Furuta family on the steps of their 1912 bungalow in Wintersburg Village, circa 1923. The Furuta farm and Wintersburg Japanese Presbyterian Mission complex is the sole remaining pre-Alien Land Law, Japanese-owned property in Huntington Beach and much of Orange County. The Mission is the oldest Japanese church in Orange County, and most of Southern California. (Photo courtesy of the Furuta family) All rights reserved. ©

The fate of Historic Wintersburg now goes before the Huntington Beach City Council on Monday, November 4 (6 p.m.). The Council will review and discuss the Environmental Impact Report (EIR) for the "Warner-Nichols" project, which proposes rezoning the property to commercial / industrial and includes an application for demolition of all six historic structures on the property.

Individuals and organizations representing thousands of concerned people from Huntington Beach, from throughout California, and from around the country have sent letters supporting the preservation of Historic Wintersburg (see support list at http://historicwintersburg.blogspot.com/2013/07/saving-american-history.html).

The significance of an extant pre-Alien Land Law of 1913 property---when Japanese immigrants were prohibited from owning property and obtaining citizenship---has prompted expert assessment that the Furuta farm and Wintersburg Japanese Presbyterian Mission complex are potentially eligible for the National Register of Historic Places. The 2011 City of Huntington Beach environmental assessment noted all six structures are potentially eligible for the National Register, the same assessment made over thirty years ago during an analysis for Caltrans in 1986.

The most recent assessment was provided after an inspection by the U.S. National Park Service in May 2013, and again in October 2013 by the National Trust for Historic Preservation. Both federal entities raised concerns about the environmental review and that preservation alternatives were not fully analyzed. The National Historic Trust for Historic Preservation notes the 2013 initiative of the U.S. Department of the Interior and National Park Service to identify and find ways to preserve Asian American and Pacific Islander heritage sites as part of the national preservation goals, and offers assistance to the City.

Letter to Huntington Beach City Council from National Trust for Historic Preservation, recommending application for the National Register of Historic Places and assistance toward finding historic preservation alternatives.

Excerpt from U.S. National Park Service technical memorandum regarding inspection of Historic Wintersburg property.

In addition to concerns about the historic significance of the property, the Ocean View School District has raised concerns about the Warner-Nichols project proposal to re-zone the majority of the land to industrial use. The area proposed for industrial zoning is at the south end of the Furuta farm, adjacent to the Oak View Elementary School and the Oak View residential neighborhood.

An overview of the Ocean View School District's concerns was reported by the Huntington Beach Independent, http://www.hbindependent.com/news/tn-hbi-me-1024-oak-view-rainbow-20131023,0,6898470.story

The congregation of the Wintersburg Japanese Presbyterian Mission, March 8, 1910. The manse was built immediately after the Mission was constructed. A glimpse of the Terahata house, which had been moved temporarily to the property, can be seen in the background. Founder Reverend Hisakichi Terasawa and future goldfish farmer Charles Furuta would be in the crowd, along with clergy from Westminster. (Photo courtesy of Wintersburg Presbyterian Church) All rights reserved. ©

"Historic places create connections to our heritage that help us understand our past, appreciate our triumphs, and learn from our mistakes. Historic places help define and distinguish our communities by building a strong sense of identity."

National Trust for Historic Preservation

LAST CHANCE: Help save American heritage by being a voice for the preservation of Historic Wintersburg at the Huntington Beach City Council meeting.

Huntington Beach City Council

6 p.m., Monday, November 4*

City of Huntington Beach City Hall - City Council Chambers

2000 Main Street

(Intersection of Main Street and Yorktown Avenue)

*Please arrive a few minutes early to fill out a speaker card for the "Warner-Nichols" project public hearing. Provide the card to the city clerk inside the Council chambers.

The fate of Historic Wintersburg now goes before the Huntington Beach City Council on Monday, November 4 (6 p.m.). The Council will review and discuss the Environmental Impact Report (EIR) for the "Warner-Nichols" project, which proposes rezoning the property to commercial / industrial and includes an application for demolition of all six historic structures on the property.

Individuals and organizations representing thousands of concerned people from Huntington Beach, from throughout California, and from around the country have sent letters supporting the preservation of Historic Wintersburg (see support list at http://historicwintersburg.blogspot.com/2013/07/saving-american-history.html).

The significance of an extant pre-Alien Land Law of 1913 property---when Japanese immigrants were prohibited from owning property and obtaining citizenship---has prompted expert assessment that the Furuta farm and Wintersburg Japanese Presbyterian Mission complex are potentially eligible for the National Register of Historic Places. The 2011 City of Huntington Beach environmental assessment noted all six structures are potentially eligible for the National Register, the same assessment made over thirty years ago during an analysis for Caltrans in 1986.

The most recent assessment was provided after an inspection by the U.S. National Park Service in May 2013, and again in October 2013 by the National Trust for Historic Preservation. Both federal entities raised concerns about the environmental review and that preservation alternatives were not fully analyzed. The National Historic Trust for Historic Preservation notes the 2013 initiative of the U.S. Department of the Interior and National Park Service to identify and find ways to preserve Asian American and Pacific Islander heritage sites as part of the national preservation goals, and offers assistance to the City.

Letter to Huntington Beach City Council from National Trust for Historic Preservation, recommending application for the National Register of Historic Places and assistance toward finding historic preservation alternatives.

Excerpt from U.S. National Park Service technical memorandum regarding inspection of Historic Wintersburg property.

In addition to concerns about the historic significance of the property, the Ocean View School District has raised concerns about the Warner-Nichols project proposal to re-zone the majority of the land to industrial use. The area proposed for industrial zoning is at the south end of the Furuta farm, adjacent to the Oak View Elementary School and the Oak View residential neighborhood.

An overview of the Ocean View School District's concerns was reported by the Huntington Beach Independent, http://www.hbindependent.com/news/tn-hbi-me-1024-oak-view-rainbow-20131023,0,6898470.story

"Historic places create connections to our heritage that help us understand our past, appreciate our triumphs, and learn from our mistakes. Historic places help define and distinguish our communities by building a strong sense of identity."

National Trust for Historic Preservation

LAST CHANCE: Help save American heritage by being a voice for the preservation of Historic Wintersburg at the Huntington Beach City Council meeting.

Huntington Beach City Council

6 p.m., Monday, November 4*

City of Huntington Beach City Hall - City Council Chambers

2000 Main Street

(Intersection of Main Street and Yorktown Avenue)

*Please arrive a few minutes early to fill out a speaker card for the "Warner-Nichols" project public hearing. Provide the card to the city clerk inside the Council chambers.

Sunday, October 13, 2013

"Our American Family" features the Furuta family of Historic Wintersburg (VIDEO)

Discussions began in January 2013 with the remarkable new public television series, Our American Family, about the history of the Furuta family of Historic Wintersburg. The program producers were looking for a family whose story is iconic for Japanese Americans, from their earliest arrival in America through their path to the present day.

The mission of Our American Family is "to document our American family heritage, one family at a time, and inspire viewers to capture their own family stories - before those voices are gone." The producers talked about their own families and the lessons we can learn from those who came before: "Every day that passes is another day closer to a day when we will no longer be able to hear first-hand what it meant to be a family during this simpler time, before the world changed. To hear first-hand what lessons were learned that we can apply today..."

Left: The Our American Family film crew near the Wintersburg Japanese Presbyterian Mission and Church buildings on the Furuta farm. (Photo, September 27, 2013)

In September 2013, filming began to capture the story of Charles Mitsuji and Yukiko Yajima Furuta, and their descendants. With the recorded oral history of the Issei-generation Yukiko Furuta---conducted thirty-one years ago in 1982---the stories and memories of five generations of the Furuta family will be heard.

The Nisei generation interviews include 91-year-old Etsuko Furuta, the daughter of Charles and Yukiko, born on the Furuta farm in Wintersburg Village, and Martha Furuta, wife of Charles and Yukiko's son, Raymond.

Right: The century-old camera used by Charles Mitsuji Furuta to take many of the images shared on Historic Wintersburg.

The Sansei generation interviews include Norman, Dave and Ken Furuta, sons of Raymond and Martha, and the grandsons of Charles and Yukiko Furuta. The Yonsei generation is represented by Michael Furuta, the great grandson of Charles and Yukiko. The oral history interviews will include historic photographs and present-day images filmed on the Furuta farm.

Historic Wintersburg is honored to be part of this effort, which shares more of the history of the Furuta family and their life in early Orange County. Their story is iconic of Japanese American settlement in the American West.

FIRST CHANCE AT CITIZENSHIP - The document certifying Charles Mitsuji Furuta had passed his citizenship class, taken at Huntington Beach High School between mid 1952 to early 1953. Congress passed the Immigration and Nationality Act in June 1952, making it possible for the first time for Japanese immigrants to become U.S. citizens. Charles Furuta passed away in October 1953, before he could realize his dream to become a naturalized citizen. (Photo, September 27, 2013)

Our American Family featuring the Furuta family will be aired in 2014 (date to be announced) on public television around the country. For readers of Historic Wintersburg, a special preview from the program's producers.

HISTORIC WINTERSBURG SPECIAL PREVIEW: OUR AMERICAN FAMILY, THE FURUTA FAMILY

Note: This excerpt starts in 1912, the year Charles Furuta married Yukiko Yajima. Charles had lived in the United States for 12 years---arriving in 1900---and, had saved enough money to buy land and build a home in Wintersburg Village. He was the first Japanese baptized into Christianity in Orange County and donated land on his farm for the Wintersburg Mission.

SUPPORT HISTORIC PRESERVATION: Like us on Facebook to stay current on Historic Wintersburg activities and history, as well as updates on special events like the airing of Our American Family, https://www.facebook.com/pages/Historic-Wintersburg-Preservation-Task-Force/433990979985360

DONATE TO THE DEDICATED PRESERVATION FUND FOR HISTORIC WINTERSBURG: http://www.huntingtonbeachca.gov/i_want_to/give/donation-wintersburg.cfm

© All rights reserved. No part of the Historic Wintersburg blog may be reproduced or duplicated without prior written permission from the author and publisher, M. Adams Urashima.

Tuesday, October 8, 2013

Huntington Beach City Council decision on fate of Historic Wintersburg postponed to Nov. 4

ABOVE: Grace Furuta, Mrs. Noji and a very good-natured Reverend Noji, with friends at Huntington Beach, circa 1939. Oil derricks line Ocean Boulevard, now Pacific Coast Highway, and a surfer can be seen carrying a board in the background. (Photo courtesy of the Furuta family) © ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

The Huntington Beach City Council review and decision on the Historic Wintersburg (Warner-Nichols) Environmental Impact Report and demolition application is re-scheduled to Monday, November 4.

Huntington Beach City Council

6 p.m., Monday, November 4

City of Huntington Beach City Hall - City Council Chambers

2000 Main Street

(Intersection of Main Street and Yorktown Avenue)

Meeting date postponed from October 7 and October 21 dates by the project applicant.

© All rights reserved. No part of the Historic Wintersburg blog may be reproduced or duplicated without prior written permission from the author and publisher, M. Adams Urashima.

The Huntington Beach City Council review and decision on the Historic Wintersburg (Warner-Nichols) Environmental Impact Report and demolition application is re-scheduled to Monday, November 4.

Huntington Beach City Council

6 p.m., Monday, November 4

City of Huntington Beach City Hall - City Council Chambers

2000 Main Street

(Intersection of Main Street and Yorktown Avenue)

Meeting date postponed from October 7 and October 21 dates by the project applicant.

© All rights reserved. No part of the Historic Wintersburg blog may be reproduced or duplicated without prior written permission from the author and publisher, M. Adams Urashima.

Thursday, September 19, 2013

Consider the settlement of America

ON THE STEPS OF THE CHURCH - Mission clergy with Wintersburg goldfish farmers commemorating the opening in 1934 of their second church at the corner of Wintersburg (Warner) Avenue and Nichols Lane, thirty years after the founding of the Mission. (Front left to right) Wintersburg Mission founder Reverend Hisakichi Terasawa, Reverend and Mrs. Kenji Kikuchi, (back row, left to right) Yukiko Furuta, Masuko Akiyama (Yukiko's sister), and

Henry Kiyomi Akiyama. Charles Furuta was behind the camera. (Photo courtesy of the Furuta family) All rights reserved. ©

"I always consider the settlement of America with reverence and wonder, as the opening of a grand scene..." ~John Adams, diary entry, November 14, 1760

In 1930, Reverend Kenji Kikuchi typed out a history of the Wintersburg Japanese Presbyterian Church, describing the Mission property as a "150 ft. by 50 ft., corner lot of church member's goldfish farm." He also notes the Mission---founded in 1904---is "one of the oldest churches in Southern California" and "the only center of the Japanese community in this vicinity."

The Church's letterhead already identifies with Huntington Beach, even though the Wintersburg District would not be annexed for another 27 years.

Excerpt from 1930 history of the Wintersburg Japanese Presbyterian Church, April 1, 1930. (Image courtesy of Wintersburg Presbyterian Church)

By 1973, a City of Huntington Beach Open Space / Conservation report identified the “Old Japanese Church” as a historical cultural landmark.

In 1983, a Cultural Resource Survey Report by Scientific Resource Surveys, Inc., for the Warner Avenue Widening and Reconstruction project identifies the Furuta farm and Wintersburg mission property as eligible for the National Register of Historic Places.

The report---written thirty years ago---states the Furuta home "represents probably the oldest surviving residential property of Orange County's pioneer Japanese community," and the Mission and Furuta farm "taken together...represented the center of the Japanese community in turn-of-the-century Orange County."

Yukiko Furuta stands on the steps of her new home in Wintersburg Village, circa 1913. The manse for the Wintersburg Japanese Presbyterian Mission can be seen at the center of the photograph, the rear edge of the Mission building at the far right. The gum trees on the property were planted by Charles Furuta. (Photo courtesy of the Furuta family) All rights reserved. ©

The Environmental Assessment for the "Warner-Nichols Project"---prepared prior to the draft Environmental Impact Report---concludes each building on the Furuta farm and Wintersburg Mission property is "potentially eligible for the National Register and California Register of Historic Places."

The 2012 draft Environmental Impact Report (EIR) acknowledges at least four structures on the Furuta farm and Wintersburg Mission property are eligible for the National Register of Historic Places. In April and August 2013, the Huntington Beach Planning Commission directed the Furuta barn be added as a local historic landmark.

The 2013 draft Historic Context Survey---a citywide historical resources survey for the City of Huntington Beach---makes the same conclusion, that at least four of the structures at Historic Wintersburg are eligible for the National Register of Historic Places.

Yukiko Furuta (left) with her sister, Masuko Akiyama, and Yukiko's son, Raymond, at the Cole Ranch in Wintersburg Village, circa 1915. The Cole Ranch was located south of Wintersburg Avenue and west of Gothard Street, in the area of the present-day Ocean View High School. (Photo courtesy of the Furuta family) All rights reserved. ©

In May 2013, the U.S. National Park Service inspected the property. A summary of their key findings was provided to the City of Huntington Beach in August:

a. The property is “potentially eligible for listing on the National Register of Historic Places under Criterion A in association with Japanese American Settlement in the American West.”

b. “Property retains a remarkable amount of integrity,” “none of the buildings are beyond repair,” “site seems to lend itself to development possibilities that could preserve and rehabilitate the historic resources.”

c. “NPS would recommend some general maintenance and stabilization of the buildings. Immediate actions that could easily be accomplished include removal of debris from roofs, cleaning trash and other debris from building interiors, securing doors and windows to keep out elements, etc. Other short-term actions that could be achieved include moth balling the buildings according to preservation standards."

d. “NPS encourages Rainbow Environmental to seek National Register of Historic Places listing for the property and to explore the various Federal and State Preservation Tax Incentive programs that could be used in the rehabilitation of the structures.”

Charles Furuta, dumping a wagon-full of sugar beets at the Smeltzer-Wintersburg siding of the Southern Pacific Railroad, circa 1914-915. The siding was located near present-day Gothard Street in north Huntington Beach. (Photo courtesy of the Furuta family) All rights reserved. ©

Pioneer history threatened

On October 7, 2013, the Huntington Beach City Council will review the issues of the draft EIR for the "Warner-Nichols Project," which proposes changing the property's zoning to commercial / industrial, and demolishing all of the historic structures of the Furuta farm and Wintersburg Japanese Presbyterian Mission complex.

For eighty-three years---since the first written history in 1930---the property has been documented as being the early 1900s center of the Japanese pioneer community in coastal Orange County. Under the California Environmental Quality Act (CEQA) under which the EIR process is governed, there must be an "overriding consideration" or justification for the demolition of historic resources. Per the City of Huntington Beach General Plan, demolition of historic resources is inconsistent with its policies.

The Warner-Nichols Project proposes no development, rather a zone change and demolition--with no description or analysis of the unknown, ultimate future use of the land---and there is inadequate analysis regarding the historical resources, archaeological sensitivities and project alternatives.

An illustration of the Ross family's arrival in Orange County, circa 1868, by descendant Glenn Swann. (Image: Pioneer Memories of the Santa Ana Valley, Vol. III, 1983)

Archaeological analysis

A history of the Ross family for the Pioneer Memories of the Santa Ana Valley, includes a report by the descendant of Josiah and Sarah Ross that "the Indians in the area had campsites in Newport Beach area and on the Costa Mesa bluffs, Huntington Beach Palisades and in the Wintersburg District. They used to skirt the more populated town and ride their ponies to Grandma's back door...she readily gave them biscuits, sometimes a little coffee and was friendly to them. They never came empty handed. Sometimes they would bring a young rabbit or a few quail and sometimes a wild duck."

The Ross family sold land in the Wintersburg District to the Cole family, resulting in the Cole Ranch (The Historical Volume and Reference Works, Vol. III, Thomas B. Talbert, Historical Publishers, 1963). In the early 1900s, Tongva artifacts were found on the Cole Ranch, such as the Universe Effigy now on display in the Bowers Museum. (See http://historicwintersburg.blogspot.com/2012/02/cole-ranch-and-universe-effigy.html)

More recently, an archaeological investigation for an ATT WiFi tower on the former Cole Ranch (now Ocean View High School) unearthed artifacts, such as a grinding stone, along with shell middens. The expert conclusion is that the land---an approximately three-minute walk from the Historic Wintersburg property---was once a Tongva settlement. Additionally, a multiple burial site was found in the 1970s only 1320 feet northwest of the Furuta farm (Shell Midden, Site Number 30000346). It is unrealistic to assume the Tongva were never on the Historic Wintersburg property.

Also not identified in the EIR, are the locations of the goldfish ponds, trash disposal areas, outhouses, and prior structures (e.g. the Terahata house temporarily on the Furuta farm), their locations being potential sources for early 1900s archaeological finds.

Despite known Tongva campsites and evidence of nearby settlement, the EIR dismisses the possibility of any findings. There has been no comprehensive field study to determine archaeological resources on the Historic Wintersburg property and the EIR does not include recent area surveys. Several professional archaeologists--with experience in Orange County and elsewhere in California--have written the City expressing their concerns and noting the EIR does not include recent archaeological studies in the area.

This 1947 aerial shows the Furuta farm and Mission complex near the center of the image, Wintersburg (Warner) Avenue running east to west, horizontally across this image. The Mission complex and Furuta home are on the southeast corner of the intersection of Wintersburg Avenue and Nichols Lane. The Nichols family home also is visible on the south side of Wintersburg Avenue, west side of Nichols Lane. Oak View Elementary School is today located in the area beyond the south end of the Furuta farm, that area then farmland and a few small buildings.

Impacts and Alternatives

Per CEQA intent and case law, projects must adequately and comprehensively analyze future land use impacts. This cannot be done when there are no development plans, segmenting the ultimate land use from the proposed project.

"We hold that an EIR must include an analysis of the environmental effects of future expansion or other action if: (1) it is a reasonably foreseeable consequence of the initial project; and (2) the initial expansion or action will be significant in that it will likely change the scope or nature of the initial project or its environmental effects." (Laurel Heights Improvement Association v. Regents of the University of California).

In Laurel Heights, the court held that an EIR must address reasonably foreseeable activities, that a project may not be segmented into smaller parts during environmental review, and that an EIR must adequately discuss project alternatives.

The appeal by the Ocean View School District regarding the planning commission recommendation to certify the EIR relates to lack of analysis regarding impacts of unknown industrial uses of the ultimate project on the adjacent Oak View Elementary School and childcare center.

The EIR did not provide a list of potential relocation sites for the historic structures and there is no documentation of analysis of sites considered and explanations why they may or may not be suitable (the Historic Wintersburg Preservation Task Force has now undertaken this task as a "plan B" measure).

The EIR also did not fully analyze the variety of adaptive reuse options, but restricted the analysis to a narrow view of adaptive reuse. The explanation that the individual structures are not conducive to proposed uses is not considering the scope of creative adaptive reuse options that can be achieved in concert with historic preservation.

Consideration of alternatives---required by CEQA and governed by the "rule of reason"---requires sufficient analysis of alternatives necessary to permit a reasoned choice. Sufficient analysis is not generally achieved in a few paragraphs without supporting documentation.

Yukiko Furuta in contemplation, circa 1914. This photograph was taken inside the Cole Ranch house, in Wintersburg. (Photo courtesy of the Furuta family)

All rights reserved. ©

Mitigation

According to the California Public Resource Code, "by definition, a substantial adverse change means, 'demolition, destruction, relocation, or alterations,' such that the significance of an historical resource would be impaired. For purposes of National Register of Historic Places eligibility, reductions in a property’s integrity (the ability of the property to convey its significance) should be regarded as potentially adverse impacts." (PRC §21084.1, §5020.1(6))

The mitigation proposed for the demolition of significant historic resources---photo documentation---is the minimal mitigation available and does not reduce the impact of demolition to "less than significant." In California, in most cases the use of drawings, photographs, and/or displays does not mitigate the physical impact on the environment caused by demolition or destruction of an historical resource (14 CCR § 15126.4(b)).

The project proposes to contact an archaeological monitor during demolition, grading and construction should there be an archaeological find. However, there will be no one qualified on the construction site to identify what is considered a "find."

Yukiko Furuta and Charles Furuta (far right) at the Cole Ranch in Wintersburg, circa 1914. (Photo courtesy of the Furuta family) All rights reserved. ©

The question remains

The National Trust for Historic Preservation reports, "across the nation a tear down epidemic is wiping out historic neighborhoods" forever changing the historic character and identity of communities.

Historic Wintersburg includes a history that many had forgotten. This five-acre property holds the history of Japanese pioneer settlement, agricultural development, Huntington Beach's mission era, the struggle for civil liberties, the achievements of those who served during wartime, and the injustice of forced evacuation and incarceration during World War II. It also holds the history of those who returned and the remarkable endurance of the human spirit.

Now that we know more of the history---and the history yet to be uncovered---the question remains: will we consider the settlement of America and will we save it for future generations?

Huntington Beach City Council

6 p.m., Monday, **NOVEMBER 4**

City of Huntington Beach City Hall - City Council Chambers

2000 Main Street

(Intersection of Main Street and Yorktown Avenue)

**Meeting date postponed from October 7 and October 21 by the project applicant.

© All rights reserved. No part of the Historic Wintersburg blog may be reproduced or duplicated without prior written permission from the author and publisher, M. Adams Urashima.

"I always consider the settlement of America with reverence and wonder, as the opening of a grand scene..." ~John Adams, diary entry, November 14, 1760

In 1930, Reverend Kenji Kikuchi typed out a history of the Wintersburg Japanese Presbyterian Church, describing the Mission property as a "150 ft. by 50 ft., corner lot of church member's goldfish farm." He also notes the Mission---founded in 1904---is "one of the oldest churches in Southern California" and "the only center of the Japanese community in this vicinity."

The Church's letterhead already identifies with Huntington Beach, even though the Wintersburg District would not be annexed for another 27 years.

Excerpt from 1930 history of the Wintersburg Japanese Presbyterian Church, April 1, 1930. (Image courtesy of Wintersburg Presbyterian Church)

By 1973, a City of Huntington Beach Open Space / Conservation report identified the “Old Japanese Church” as a historical cultural landmark.

In 1983, a Cultural Resource Survey Report by Scientific Resource Surveys, Inc., for the Warner Avenue Widening and Reconstruction project identifies the Furuta farm and Wintersburg mission property as eligible for the National Register of Historic Places.

The report---written thirty years ago---states the Furuta home "represents probably the oldest surviving residential property of Orange County's pioneer Japanese community," and the Mission and Furuta farm "taken together...represented the center of the Japanese community in turn-of-the-century Orange County."

Yukiko Furuta stands on the steps of her new home in Wintersburg Village, circa 1913. The manse for the Wintersburg Japanese Presbyterian Mission can be seen at the center of the photograph, the rear edge of the Mission building at the far right. The gum trees on the property were planted by Charles Furuta. (Photo courtesy of the Furuta family) All rights reserved. ©

The Environmental Assessment for the "Warner-Nichols Project"---prepared prior to the draft Environmental Impact Report---concludes each building on the Furuta farm and Wintersburg Mission property is "potentially eligible for the National Register and California Register of Historic Places."

The 2012 draft Environmental Impact Report (EIR) acknowledges at least four structures on the Furuta farm and Wintersburg Mission property are eligible for the National Register of Historic Places. In April and August 2013, the Huntington Beach Planning Commission directed the Furuta barn be added as a local historic landmark.

The 2013 draft Historic Context Survey---a citywide historical resources survey for the City of Huntington Beach---makes the same conclusion, that at least four of the structures at Historic Wintersburg are eligible for the National Register of Historic Places.

Yukiko Furuta (left) with her sister, Masuko Akiyama, and Yukiko's son, Raymond, at the Cole Ranch in Wintersburg Village, circa 1915. The Cole Ranch was located south of Wintersburg Avenue and west of Gothard Street, in the area of the present-day Ocean View High School. (Photo courtesy of the Furuta family) All rights reserved. ©

In May 2013, the U.S. National Park Service inspected the property. A summary of their key findings was provided to the City of Huntington Beach in August:

a. The property is “potentially eligible for listing on the National Register of Historic Places under Criterion A in association with Japanese American Settlement in the American West.”

b. “Property retains a remarkable amount of integrity,” “none of the buildings are beyond repair,” “site seems to lend itself to development possibilities that could preserve and rehabilitate the historic resources.”

c. “NPS would recommend some general maintenance and stabilization of the buildings. Immediate actions that could easily be accomplished include removal of debris from roofs, cleaning trash and other debris from building interiors, securing doors and windows to keep out elements, etc. Other short-term actions that could be achieved include moth balling the buildings according to preservation standards."

d. “NPS encourages Rainbow Environmental to seek National Register of Historic Places listing for the property and to explore the various Federal and State Preservation Tax Incentive programs that could be used in the rehabilitation of the structures.”

Pioneer history threatened

On October 7, 2013, the Huntington Beach City Council will review the issues of the draft EIR for the "Warner-Nichols Project," which proposes changing the property's zoning to commercial / industrial, and demolishing all of the historic structures of the Furuta farm and Wintersburg Japanese Presbyterian Mission complex.

For eighty-three years---since the first written history in 1930---the property has been documented as being the early 1900s center of the Japanese pioneer community in coastal Orange County. Under the California Environmental Quality Act (CEQA) under which the EIR process is governed, there must be an "overriding consideration" or justification for the demolition of historic resources. Per the City of Huntington Beach General Plan, demolition of historic resources is inconsistent with its policies.

The Warner-Nichols Project proposes no development, rather a zone change and demolition--with no description or analysis of the unknown, ultimate future use of the land---and there is inadequate analysis regarding the historical resources, archaeological sensitivities and project alternatives.

An illustration of the Ross family's arrival in Orange County, circa 1868, by descendant Glenn Swann. (Image: Pioneer Memories of the Santa Ana Valley, Vol. III, 1983)

Archaeological analysis

A history of the Ross family for the Pioneer Memories of the Santa Ana Valley, includes a report by the descendant of Josiah and Sarah Ross that "the Indians in the area had campsites in Newport Beach area and on the Costa Mesa bluffs, Huntington Beach Palisades and in the Wintersburg District. They used to skirt the more populated town and ride their ponies to Grandma's back door...she readily gave them biscuits, sometimes a little coffee and was friendly to them. They never came empty handed. Sometimes they would bring a young rabbit or a few quail and sometimes a wild duck."

The Ross family sold land in the Wintersburg District to the Cole family, resulting in the Cole Ranch (The Historical Volume and Reference Works, Vol. III, Thomas B. Talbert, Historical Publishers, 1963). In the early 1900s, Tongva artifacts were found on the Cole Ranch, such as the Universe Effigy now on display in the Bowers Museum. (See http://historicwintersburg.blogspot.com/2012/02/cole-ranch-and-universe-effigy.html)