Southern Pacific Railroad tracks disappearing into the urban wilds of present-day Huntington Beach. (Photo, June 16, 2013) © All rights reserved.

~Updated January 2015~

Researching local history sometimes requires ducking into dusty, old buildings, brushing away cobwebs and doing a little mental time travel to get a sense of the people who came before.

And, sometimes it requires one to channel one's inner hobo. Looking for the history of Wintersburg Village, California State University - Fullerton grad student historian Tom Fujii and I walked the celery train line from Smeltzer to the Ellis bridge. Instead of a bindle, we carried digital cameras, water and brushes to uncover the traces of history left behind on the Southern Pacific Railroad.

RIGHT: Loading celery into Ventilator cars at the Smeltzer station, once located along present-day Gothard Avenue in Huntington Beach, circa 1901. (Photo courtesy of the Orange County Archives)

The rail line originally was built by the predecessor to the Southern Pacific Railroad, the Santa Ana & Newport Railway, in 1897 before being acquired by Southern Pacific in 1899.

Left: The Santa Ana to Newport and Smeltzer to Huntington Beach branches were planned to complete a loop through key points in Orange County. (Source: When the Railroad Leaves Town, American Communities in the Age of Rail Line Abandonment: Western United States; Joseph P. Schwieterman; Truman State University Press, 2004)

In 1901, the Southern Pacific reported to the California Railroad Commissioners they owned 10.76 miles of track between Newport Beach and Smeltzer. By 1907, the Southern Pacific extended the Smeltzer branch to Stanton. Trainload after trainload of produce grown in the peat lands of Smeltzer and Wintersburg (both present-day Huntington Beach) left for East Coast markets.

RIGHT: A horse-drawn sugar beet wagon is driven up a ramp by Charles Mitsuji Furuta of Wintersburg Village, with a wagon-load of sugar beets to unload on the Smeltzer siding, circa 1914-1915. (Photo courtesy of the Furuta family) © All rights reserved.

LEFT: A moment later, the wagon-load of sugar beets is dumped into the rail car. The railroad siding at Smeltzer and Wintersburg Village helped get produce to market and contributed to the development of small communities in Orange County. (Photo courtesy of the Furuta family) © All rights reserved.

The Southern Pacific Company was organized in 1884, with Collis Huntington serving on the board in New York and Henry Huntington in San Francisco. When Henry Huntington didn't succeed Collis Huntington as president of the Southern Pacific, he founded the Pacific Electric Railway, remaining on the board, selling his shares to finance his new railway.

Henry Huntington later brought the Pacific Electric Railway into "Pacific City," promptly renamed Huntington Beach to honor his investment in the growing village. These are the rail lines into which flowed the people, produce and money that created Orange County.

The Southern Pacific had already gained a tycoon-era reputation by the time it arrived in Orange County. Some editorials of the late 1800s depicting the company as an octopus, acquiring vast tracts of land and manipulating its development along the railroad lines.

LEFT: "The Curse of California," from The Wasp, August 19, 1882, gives some perspective on what a large number of Californians thought about the railroad tycoons. (Image, Wiki Commons)

In 1904, a blackmailer demanding $10,000 threatened the Southern Pacific with blowing up its tracks and derailing trains somewhere between Stockton and Los Angeles. The company placed armed guards along the tracks and on its trains, and sent Pinkerton security forces "dressed in rags" to mingle with hobos.

LEFT: The San Francisco Call reports how Huntington Beach's namesake, Henry Huntington (far right in the front-page photos at left), ousted one Southern Pacific Company president for another, with plans to "resume the political game in this state." (Chronicling America, San Francisco Call, August 18, 1901)

Nevertheless, the farmers in Smeltzer and Wintersburg were happy to see the train, as it meant they could get their crops to market. Henry Winters, for whom Wintersburg was named, donated land for the Wintersburg siding of the Southern Pacific. The train was necessary to create commerce and bring people and business to the growing town sites along the coast.

Orange Countian Merle Ramsey describes the County when he arrived in 1902, "Hunting, fishing, and the outdoor life substituted for today's more hectic pastimes. Schools were simple and a pleasant way to get to know people with whom you would work and live the rest of your life. There was little emphasis on, nor opportunity for, higher education -- beyond grade or high school. There was a great deal of emphasis on the brawn and muscle types of work necessary for survival."* The railroad was one of the first signs of the outside, urban world entering Orange County.

Right: Along the Smeltzer Branch line, Carnegie steel used on the celery train line into the early 1900s. Carnegie sold his company to J.P. Morgan in 1900, beginning Carnegie's remarkable philanthropic efforts across America. (Photo, June 2013) © All rights reserved.

During the early to mid 20th Century, the rail line was handed back and forth between rail companies. Henry Huntington sold the Pacific Electric Railway to the Southern Pacific in 1911 (except for the Los Angeles Railway), resulting in the "great merger of 1911." The section of rail line south of Wintersburg (Warner) Avenue was abandoned by Southern Pacific in 1933. It was later picked up by the Pacific Electric Railway along with the rest of the Smeltzer Branch line in 1948. The Pacific Electric used this line for freight service to its coastal track, calling it the Huntington Beach Branch.

In the mid 1960s, Southern Pacific acquired the Pacific Electric lines, leading to their demise. In 1976, Southern Pacific abandoned the rail line through downtown Huntington Beach, making Wintersburg once again the last maintained branch of the line. By 1993, the Southern Pacific rail line south of Ellis Avenue was removed for residential development, leaving a rail bridge to nowhere.

Right: Railroad ties now at rest, once supported the train line that fueled north Orange County's agricultural and economic boom. (Photo, June 16, 2013) © All rights reserved.

The peat lands and "Willows" area of Smeltzer---in what is now north Huntington Beach---is described in a 1989 U.S. Army Corps of Engineers (USACE) historical analysis of the Bolsa Chica and Huntington Beach mesas as "giving refuge to ducks, geese and birds and provided cover for wildcats, raccoons, feral hogs, coyotes and badgers. Rattlesnakes, whose habitat was the upland mesa, sometimes floated in on flood waters."

SMELTZER: Remnants of the Smeltzer Branch line near Golden West College in north Huntington Beach. Once surrounded by celery, sugar beet and chili pepper fields, the area is now populated with retail shopping, restaurants and homes. A mid 1800s labor camp in this area once housed hundreds of agricultural workers. (Photo, 2012) © All rights reserved.

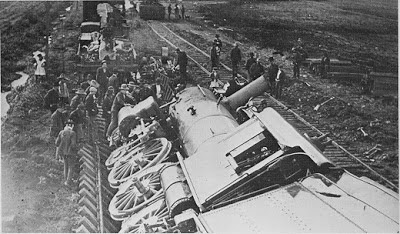

SMELTZER: The soft peat soil plus a heavy train equaled a bad day on the Southern Pacific celery line in Smeltzer, circa 1901. Tracks along the beach were equally challenging when ocean storms or flooding washed out the line. (Photo, ucf.berkeley.edu)

SMELTZER - An aerial of a warehouse in Smeltzer, next to the Southern Pacific Railroad line, circa 1947. (Photo courtesy of the Orange County Archives)

The USACE report describes Smeltzer as having "a store, a small hotel, a telephone office, blacksmith's forge, and a barn large enough for 50 teams of horses."

It's in this area that D.E. Smeltzer and E.A. Curtis leased in the late

1800s a reported 80 acres to plant celery, contracting with Chinese

laborers and working for the Earl Fruit Company.

Historian Leo J. Friis writes that D.E. Smeltzer found "wild celery growing luxuriantly in the peat lands of Orange County," prompting him to introduce celery growing to the area.

Smeltzer and Curtis provided bunk housing for their Chinese laborers. They were continually harassed and their living quarters burned down, requiring Smeltzer and Curtis to hire a guard to protect them. They persisted and managed to make a profit.**

After the Southern Pacific Railroad built the 11-mile track from Newport Beach to Smeltzer in 1902, 1800 carloads of celery grown in Smeltzer and Wintersburg shipped out to market.

"Celery

culture exceeded 275,000 acres, becoming one of the major industries of

the county, extending from the peat bogs over a large part of the

'Willows,'" continues the USACE report. Celery began to decline around 1906, when celery blight hit the fields.

WINTERSBURG - At Warner (once Wintersburg) and Gothard avenues, in the area where celery, sugar beets, and beef were loaded into train cars. Just east of the tracks, the Tashima Market (formerly Asari Market) provided Wintersburg Village with staple goods, seed and feed. (Photo, May 2013) © All rights reserved.

South of Wintersburg Avenue and west of the railroad tracks was the McIntosh cattle ranch, which supplied beef for the packing plant along the rail line.

The McIntosh family--originally from Prince Edward Island in eastern Canada--was the primary supplier and manager of the Beach Packing Plant, part of the Alpha Beta company. Offering a beef market in Wintersburg frequented by Yukiko Furuta and other families in the area, the McIntosh brothers also owned a butcher shop in downtown Huntington Beach, at 126 Main Street.

WINTERSBURG: The McIntosh family provided beef for the Beach Packing Plant in Wintersburg along the Southern Pacific Line, J.W. McIntosh managing the plant for Alpha Beta. Descendent Douglas McIntosh annotated this image in red to show the location of the McIntosh house (center right) and the Furuta farm and Wintersburg Presbyterian Mission complex (upper left), as it looked in 1952. The houses at the front were referred to as "Gopher City" and were home to stockyard and packing plant employees.(Photo, The Alpha Beta Story, Esther R. Cramer; Anderson, Ritchie & Simon, 1973; special thanks to Douglas McIntosh)

WINTERSBURG: At the Beach Packing Plant in Wintersburg, from left, Herb Archie Straw, Genevieve Straw McIntosh, and David McIntosh (father of descendant Douglas McIntosh), circa 1940s. (Photo courtesy of Douglas McIntosh) © All rights reserved.

WINTERSBURG TO HUNTINGTON BEACH: Continuing south on the tracks at Talbert Avenue. Heading east on Talbert Avenue leads to the center of the former "Gospel Swamp," where settlers established a general merchandise store and post office, delivering mail by horse and buggy. (Photo courtesy of Tom Fujii, June 16, 2013) © All rights reserved.

SANTA ANA - HUNTINGTON BEACH: The railway line running from Santa Ana, through Talbert (Fountain Valley) and on to Huntington Beach was built in 1907 by the Pacific Electric Land Company. Spur lines served Huntington Beach's large sugar beet industry and the Holly Sugar Company processing facility near present-day Main Street and Gothard. The line began to decline when Holly dismantled its sugar production plant in the 1920s, after the discovery of oil in Huntington Beach. (Image, 1981 Inventory of Pacific Electric Routes, Caltrans)

Merle Ramsey thought California looked like "Paradise," when he first arrived. "No snow to wade through or shovel, no wood to chop or to lug in to take the chill off the long, cold, wintry nights; no horses to feed on the frosty mornings or evenings; no hogs to 'slop' daily, come fair weather or foul--what a delight!"

Ramsey continues, "Wages were low--but so were living costs. We can remember when twenty five cents would buy enough steak for a family of five, when haircuts were fifteen cents for men and ten cents for boys, when a penny bought a good lead pencil, when hot dogs were one and two cents each, when the roundtrip fare from Santa Ana to Newport Beach on the Southern Pacific Railway was twenty five cents and when ten cents would buy a full box of oranges from the packing house."*

WINTERSBURG TO HUNTINGTON BEACH: Along this colorful stretch of the tracks, the rail line is still fairly clear with a few weeds growing between the rails here and there. This section of the Smeltzer-Wintersburg line was used more recently. (Photo, June 16, 2013) © All rights reserved.

WINTERSBURG TO HUNTINGTON BEACH: As we continue further south, we find older tracks, and the creeping urban wilderness taking over. (Photo, June 16, 2013) © All rights reserved.

WINTERSBURG TO HUNTINGTON BEACH: We enter a beautiful stretch of the Southern Pacific historical tracks into Huntington Beach, almost requiring a machete. (Photo, June 16, 2013) © All rights reserved.

HUNTINGTON BEACH: Pampas grass, bougainvillea, palms, and prickly pear cactus can be found along the line. The rail line--south of Talbert and north of Ellis avenues--continues under the brush. (Photo, June 16, 2013) © All rights reserved.

ON THE LINE: One of the early businesses served by the railroad in Huntington Beach was the Holly Sugar Company, beginning in 1911. The factory was in the vicinity of Main, Garfield and Gothard streets. There remains a Holly Lane in this area. (Photo, City of Huntington Beach archives)

DISAPPEARING HUNTINGTON BEACH: This photograph of the Holly Sugar Company office building was taken in the early 1980s, when it hosted a church organization. The building has since been demolished. Photographer John Totten says, "I remember this building...at least one other

Holly Sugary building survived at this time. It was located on a 45

degree angle to the (Southern Pacific) main. The refinery located the building in this

orientation to accommodate the necessary track work. Being one of the

few buildings standing in this area at this time, it stood out on the

landscape due to its weird alignment. (Photograph courtesy of John Totten) © All rights reserved.

"Walking the Smeltzer Line made me think about

how this rail system helped the growing Japanese community of Wintersburg," remarks Tom Fujii of the village that became part of Huntington Beach. "It formed into a bustling farming center for sugar beets and celery.

Local farmers used animals and hand tools in planting and harvesting crops.

There existed one modern phenomenon and it was a train..."

"This is a brief encounter with a rail system that

went through Huntington Beach, time forgotten, and requires

historical preservation," concludes Fujii.

HUNTINGTON BEACH: In some places, mature trees are growing into and around the steel tracks. (Photo, June 16, 2013) © All rights reserved.

HUNTINGTON BEACH: California's state flower, the poppy, springs up along the rails. (Photo, June 16, 2013) © All rights reserved.

HUNTINGTON BEACH: Crossed ties indicate the "end of the line" ahead, near the Ellis Avenue bridge. Spur lines served as freight lines for the mammoth Holly Sugar Company once located near the intersection of Main Street and Gothard Avenue. (Photo, June 16, 2013) © All rights reserved.

HUNTINGTON BEACH: The rail bridge over Ellis Avenue once rattled with the sound of trains, is now a quiet place to reflect. The rails and ties are removed from this section, once used by the Pacific Electric Railroad (Southern Pacific by then) for a freight line to its Huntington Beach station. The Electric Railway Historical Association reports, "sugar beets brought considerable carloads down the

Wiebling branch in the old days, and when oil was discovered at

Huntington Beach, PE did a land office business moving in materials and

taking out black gold by the carload." (Photo, June 16, 2013) © All rights reserved.

HUNTINGTON BEACH: The former Southern Pacific and Pacific Electric rail bridge over Ellis Avenue--a later addition to the early 1900s line--is a perfect place for historical signage noting the legacy of Henry Huntington and the railroad in Huntington Beach. (Photo, June 16, 2013) © All rights reserved.

HUNTINGTON BEACH: Just south of the bridge, the railway easement is still evident in a magical, grassy area on the edge of a gated housing community. There is no general public access to this "ghost line" easement for the Southern Pacific and Pacific Electric. (Photo, June 16, 2013) © All rights reserved.

"Today, Southern Pacific Railroad’s Smeltzer Line

is unidentifiable unless it upsets your water bottle in the cup holder as you

drive over the rails," jokes Tom Fujii. "One wonders how it ended this way."

HUNTINGTON BEACH BACK TO SMELTZER: A Southern Pacific Railroad pamphlet, California South of Tehachapi, circa 1904, describes the Newport to Smeltzer branch line and the surrounding peat lands "where you can grow almost anything." In another section of the pamphlet, it remarks "Southern California is a land of celery, for celery flourishes in the lowlands south of Los Angeles, and it is a land of salt to season that celery with" (a reference to the desert salt beds).

WINTERSBURG: Charles Furuta, left, in a field of celery on the Cole Ranch in Wintersburg, circa 1914. Located in the area where Ocean View High School is today--south of Warner Avenue and west of Gothard Avenue and the Southern Pacific Railroad tracks--this area once was a Milling Stone Culture village. (Photo courtesy of the Furuta family) © All rights reserved.

*It was...Mission Country, Orange County California, The Reflections in Orange of Merle and Mabel Ramsey, Mission Printing Company, Laguna Beach, CA, 1973.

**Orange County Through Four Centuries, Leo J. Friis, Pioneer Press, Santa Ana, CA, 1965.

© All rights reserved.

No part of the Historic Wintersburg blog may be reproduced or duplicated

without prior written permission from the author and publisher, M. Adams

Urashima.