Huntington Beach City Attorney Michael Gates announced to local media on Friday, September 25, that the City of Huntington Beach intends to appeal the Orange County Superior Court decision that rendered moot the "Warner-Nichols" project Environmental Impact Report and determined the City violated the California Environmental Quality Act (CEQA).

Orange County Superior Court Judge Gail Andler ordered Huntington Beach on June 2, 2015, to rescind within 45 days the 2013 CEQA action---the Environmental Impact Report (EIR)---that rezoned the Historic Wintersburg property to commercial / industrial and included the approval for demolition. Read our June 2, 2015, post with associated media coverage at http://historicwintersburg.blogspot.com/2015/06/court-orders-city-to-rescind-2013-ceqa.html

Local media were informed Huntington Beach does not plan to return the commercial / industrial zoning, but wants to have the language regarding a CEQA violation removed. We cannot confirm the City's intention until the appeal is filed within the next couple weeks and the actual appeal language is available.

RIGHT: Aerial view of Historic Wintersburg, the former Furuta farm and Wintersburg Japanese Mission complex. The residential neighborhood of Oak View can be seen to the east, the Oak View Elementary School to the south, and industrial operations to the west. Across Warner Avenue is a private school. (Photograph courtesy of Huntington Beach High School alumni Fred Emmert, Class of 1960, owner of AirViews.com) © All rights reserved.

In 2012, Historic Wintersburg Preservation Task Force chair Mary Urashima commented, "the draft EIR segments the future land development plans from the current proposal to change the zoning to industrial / commercial. The draft EIR also separates the onsite structures for historic analysis. While the majority of structures meet state and federal historic criteria for listing, the entire site and collection of buildings should be evaluated as a historic district due to its age, the progression of extant buildings, and unique history."

LEFT: The 1912 Furuta bungalow as viewed through the barn, the last pioneer barn left in Huntington Beach. The sun room of the Furuta bungalow is where Charles Furuta was interrogated by the FBI following the attack by Japan at Pearl Harbor. He was taken to the Huntington Beach jail, then the Tuna Canyon Detention Station, then to the Lordsburg New Mexico military detention center, then after more than a year, reunited with his family at the Colorado River Relocation Center at Poston, Arizona. Like other Japanese Americans, he was never found to have committed any act against the United States. (Photograph by M. Urashima, 2014) © All rights reserved.

Other comments provided in 2012 on the Warner-Nichols EIR included:

--Why is the future use separated from the application for demolition and the zone change? How can the public make a decision regarding a change to the General Plan and regarding a future proposed development and its impacts? What General Plan policies encourage increasing an industrial footprint adjacent to an elementary school and residential uses? The fundamental intent of CEQA is to allow the public to review the plan in its entirety, without “piecemealing” the process. What necessitates demolition? What is the project?

--The Warner-Nichols EIR stated its goal was "establishing land use and zoning designations that are compatible with the adjacent existing commercial and industrial uses to the west and southwest of the project site. Providing a buffer to limit conflicts between the commercial and industrial uses to the west and the existing residential neighborhood to the east." How will the proposed project impact Oak View? How can the public review and consider unknown industrial / commercial plans? How do the applicant’s objectives meet the City of Huntington Beach General Plan policies?

--To quote the City’s own analysis, “The proposed project would conflict with applicable General Plan policies adopted for the purpose of avoiding or mitigating an environmental effect. Demolition of historic resources, as proposed by the project, is not consistent with the City’s General Plan goals, objectives, and policies that encourage protection, preservation, and retention of historic resources. The inconsistency with the City’s resource protection policies is a significant adverse impact that cannot be mitigated to a level of less than significant.” Why approve a project that conflicts with General Plan policy?

LEFT: An introduction to the history, Historic Wintersburg in Huntington Beach authored by Mary Adams Urashima, chair of the preservation effort, was published in March 2014 with History Press.

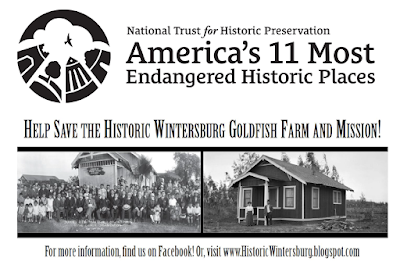

By 2013, the property had been inspected by representatives from the National Park Service, who stated the historic property retained "remarkable integrity." It also was inspected in 2014 by the National Trust for Historic Preservation, which named Historic Wintersburg one of America's 11 Most Endangered Historic Places in June of that year. Read the announcement from the National Trust at http://www.preservationnation.org/who-we-are/press-center/press-releases/national-trust-for-historic-7.html

"The site contains six extant pioneer structures and open farmland, and is one of the only surviving Japanese-owned properties acquired prior to California’s anti-Japanese 'alien' land laws of 1913 and 1920, which restricted land ownership by immigrant populations," announced the National Trust in June 2014. "In contrast to Japanese American confinement sites from the World War II era, Historic Wintersburg represents the daily community life and spiritual institutions of Japanese settlers as they established a new life in America."

RIGHT: In 2015, after two years of development, Our American Family: The Furutas of Historic Wintersburg, was screened at the Japanese American National Museum before airing nationally on public television stations. The preview can be viewed at http://www.ouramericanfamilytv.com/

“Historic Wintersburg is a unique cultural site that tells the important story of early Japanese American immigrants as they sought to make a new life and build a community in Southern California,” said Stephanie Meeks, president of the National Trust, “We strongly support a collaborative effort that preserves Wintersburg’s historic landscape while building upon its longstanding role as an educational and supportive space for the Huntington Beach community.”

LEFT: A film screening and panel discussion at the Japanese American National Museum in Little Tokyo, Los Angeles, California, for the public television program Our American Family: The Furutas. The screening was held in February 2015 for the annual Day of Remembrance held at the Museum, the 73rd anniversary of Executive Order 9066 which mandated the forced removal and incarceration of Japanese Americans on the West Coast. (Photograph courtesy of Asian Pacific Islander Historic Preservation Forum) © All rights reserved.

By 2015, a historic resources survey conducted by Galvin Preservation Associates and received by the Huntington Beach City Council acknowledged the six structures at Historic Wintersburg met criteria for the National Register of Historic Places. Also in June 2015--after the community raised $30,000 to fund the effort--the National Trust assisted with a technical analysis of Historic Wintersburg with the Urban Land Institute (ULI). The results of the analysis and ULI's recommendations are expected by the first part of October 2015.

From the Friday, September 25, 2015, Huntington Beach Independent: "Mary Urashima, chairwoman of the Historic Wintersburg Preservation Task Force, said that she and other preservationists will continue their efforts to protect the site. 'It has already been recognized nationally as a rare and significant place in American history," she said. "We hope the city and all the stakeholders will continue to work with us on that effort.'"

Read the full article from the Huntington Beach Independent at http://www.hbindependent.com/news/tn-hbi-me-1001-wintersburg-appeal-20150925,0,3176784.story

As we have said many years now, we will continue our effort to save and preserve Historic Wintersburg, one of America's 11 Most Endangered Historic Places. We're just getting started.

All rights reserved. No part of the Historic Wintersburg blog may be reproduced or duplicated without prior written permission from the author and publisher, M. Adams Urashima.