All rights reserved. No part of the Historic Wintersburg blog may be reproduced or duplicated without prior written permission from the author and publisher, M. Adams Urashima.

Thursday, July 19, 2012

A Century Later: Wintersburg

All rights reserved. No part of the Historic Wintersburg blog may be reproduced or duplicated without prior written permission from the author and publisher, M. Adams Urashima.

Thursday, July 12, 2012

Wintersburg: What will be lost?

author of The Economics of Historic Preservation: A Community Leader’s Guide

(The National Trust for Historic Preservation, 1994)

- Direct a complete California Environmental Quality Act (CEQA) analysis of all historic preservation alternatives, including both preservation in situ (onsite) and relocation for preservation

- Make the historic preservation of the century-old "Warner-Nichols" Wintersburg property a priority

- Deny demolition of historically significant buildings located on the Warner-Nichols property, including the Furuta family home and barn, and the Wintersburg Japanese Presbyterian Mission, manse and Church

- Go to http://huntingtonbeachca.gov/HBPublicComments/

- Click on "Make a service request - Agenda & Public Hearing Comments"

- Select request: "Comment"

- Select: "City Council - Agenda & Public Hearing Comments"

- You may attach a letter/document, or, write your comments in the comment form

- Your comments are automatically forwarded to all city council members, the city manager's office and the city clerk's office

Editor's note: Readers can find the full article, Economic Benefits of Preservation Session, “Sustainability and Historic Preservation by Donovan Rypkema posted on the website of the Preservation Action Council of San Jose at http://www.preservation.org/rypkema.htm

All rights reserved. No part of the Historic Wintersburg blog may be reproduced or duplicated without prior written permission from the author and publisher, M. Adams Urashima.

Wednesday, March 28, 2012

Voices from the past: Part Three, The oral histories

Present-day north Huntington Beach includes the former Wintersburg Village area. The Furuta home and barn, as well as the Wintersburg Japanese Presbyterian Mission, Church and manse--at Warner (formerly Wintersburg) Avenue and Nichols Lane--have been called the "most significant extant Japanese American site in Orange County." The earliest structures are over 100 years old--and the 1934 Church is over 80 years old.

In Voices from the past Part 3 of 4, Arthur A. Hansen---delivering the keynote address at the 2008 annual Manzanar Pilgrimage at the Manzanar National Historic Site in Inyo County, California (Photo by Gann Matsuda of the Manzanar Committee)---discusses how the oral histories were conducted.

RIGHT: Rev. and Mrs. Kikuchi stayed at the manse of the Wintersburg Japanese Presbyterian Mission from 1926 - 1936, through the Depression and the construction of the new Church at the corner of Wintersburg Avenue and Nichols Lane. See "The Wintersburg Mission," Feb. 20, 2012 post, http://historicwintersburg.blogspot.com/2012/02/wintersburg-mission-japanese.html © ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

The interview with Rev. Kikuchi at his home in Huntington Beach (conducted Aug. 26, 1981), was the first interview conducted by me with an Issei. However... I had conducted one with Charles Ishii eight days earlier. Mr. Ishii was a longtime friend of Rev. Kikuchi and gave me excellent background information relative to the early years of the Japanese American community in Orange County and to Rev. Kikuchi himself. Mr. Ishii also took me on an extensive driving tour of Orange County in which he pointed out and discussed significant historic sites bearing on the County's Nikkei experience.

I recall that the Kikuchi home was located in a very well kept neighborhood and also that it was tastefully furnished and decorated. Upon my arrival that particular afternoon, I was greeted not only by Rev. Kikuchi, but also his wife, Yukiko, and a young Sansei (third generation Japanese American), who I believe was the Kikuchi's grandson.

At the time of the interview, Rev. Kikuchi--born in Japan in 1898--was eighty-three years old. While mentally alert, he was then experiencing an assortment of health problems.

It was a great blessing, therefore, that Rev. Kikuchi's Issei wife, Yukiko, sat through the entire interview. She relayed my English-language questions to her husband in Japanese and often accompanied them with helpful interpretive gestures. Much of the interview's success, in fact, is attributable to Mrs. Kikuchi, at time an equal partner narrator.

Notwithstanding Rev. Kikuchi's health challenges, he radiated a warmth and good cheer rarely seen by me in any other people I have met in and out of interviewing settings. It was both an honor and a pleasure to become acquainted with him and to interview him.

Rev. Kikuchi's taped testimony was very enlightening about virtually every phase of the community life of Japanese Americans in Orange County, but most especially for the period from the mid 1920s--when Rev. Kikuchi assumed his ministerial duties for the Wintersburg Japanese Presbyterian Mission--through the mid-1930s, when he moved from Orange County.

Henry Kiyomi Akiyama and his wife, Masuko. Masuko was the sister of Yukiko Furuta; the Akiyamas had lived with the Furutas when they first married (Furuta home on Warner Avenue at Nichols Lane). See "Full of hope for a new life", March 4, 2012 post, http://historicwintersburg.blogspot.com/2012/03/full-of-hope-for-new-life-in.html © ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

The three interview sessions with Henry Kiyomi Akiyama at his Westminster home were conducted when Mr. Akiyama was ninety-four years old (conducted June 10, 29, and July 27, 1982) . He was born in Japan in 1888.

...We were met by Sumi Akiyama, a Nisei who lived on the same property, in a separate house, with her husband--Henry Akiyama's Nisei son, Joe Akiyama. The size of the property appeared to be about one to one and one-half acres. In addition to the two houses, there was the Pacific Goldfish Farm, which the family (first Henry, then Joe) had been operating for sixty years. (Editor's note: Akiyama's first goldfish farm was in Wintersburg, see "Goldfish on Wintersburg Avenue," Feb. 11, 2012 post, http://historicwintersburg.blogspot.com/2012/02/goldfish-on-wintersburg-avenue.html)

Sumie Akiyama, who had coordinated all the arrangements for the interview with her father-in-law, led Mrs. Gamo and me...into the expansive living room, which was tastefully appointed and contained a large fireplace and open-beam ceiling. Looking out into the patio, I could see a lawn and, behind it, an expansive vegetable garden.

Mr. Akiyama, balding and wearing spectacles, was dressed in a grey checked shirt, charcoal alpaca sweater, and grey slacks. Throughout the interview session, which lasted three hours, he was totally alert.

During the interview (Sumie Akiyama) had apparently been harvesting vegetables in the garden for Mrs. Gamo and me, because she proceeded to give us each a sizable bag filled with luscious vegetables. Whereas my bag contained mostly familiar American vegetables--green beans, squash, tomatoes and celery--Mrs. Gamo's appeared to be full of Asian vegetables such as daikon (giant white radishes), kabu (turnips), satsumaimo (sweet potatoes), and ninjin (carrots).

Sumie and Henry Akiyama toured me around the outside grounds, as well as the large greenhouse on their shared property. I soon discovered that Mr. Akiyama, in spite of his advanced age, still nurtured an enormous variety of bonsai trees and raised numerous vegetables for the family's consumption (including a mountain variety of yam, nagaimo, indigenous to his native Nagano prefecture in Japan).

We held two subsequent interview sessions with Mr. Akiyama (in 1982). I prepared for these by reading W. Manchester Boddy's Japanese in America (1921); Robert A. Wilson's and Bill Hosokawa's, East to America: A History of the Japanese in the United States (1980); and Donald Keene's Living Japan: The Land, the People, and Their Changing World (1958).

Mr. Akiyama's son, Joe, supplied me with background information about his father's business career and the Akiyama family history. We were impressed by Mr. Akiyama's prodigious memory and his penetrating insight, particularly in relationship to the goldfish farming business and the Nikkei community organizations in which he had participated before the outbreak of WWII.

When the transcript of Mr. Akiyama's interview was returned to him in 1986 (for proofing and corrections), we learned his health had slipped a great deal. Most of the changes on the transcript were made by other members of the Akiyama family.

LEFT: Mrs. Yukiko Furuta, wife of Charles M. Furuta, circa 1950s-1960s. Yukiko moved to America to marry C.M. Furuta when she was 17. She would take the "red car" (Pacific Electric Railroad) into Los Angeles for shopping and later became an avid Los Angeles Dodgers fan. See "At home in Wintersburg," Feb. 22, 2012 post, http://historicwintersburg.blogspot.com/2012/02/at-home-in-wintersburg-one-of-few.html © ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

The interview with Yukiko Furuta, the Issei widow of Charles M. Furuta, was conducted by me, along with translator Yasko Gamo, in two sessions (June 17 and July 6, 1982). I looked forward to this interview with the sister-in-law of the prominent Orange County Issei, Henry Kiyomi Akiyama, whom we had finished interviewing only one week earlier. I wanted to counterbalance the two male Issei interviews with an interview from the perspective of an Issei woman.

A second cause for my excitement was my deep-seated longing to look around Mrs. Furuta's home on Warner Avenue in Huntington Beach, formerly Wintersburg, which her late husband Charles had built for her in anticipation of her arrival from Japan in 1912 as his seventeen-year-old bride. I also wanted to get a close look at the historic Wintersburg Japanese Presbyterian Church and adjacent manse structures, which I had been informed were still standing on the five-acre Furuta property.

To prepare, I telephoned Mrs. Furuta's daughter-in-law, Martha Furuta, the wife of Mrs. Furuta's son, Ray. She provided me with an excellent background of the Furuta family and of the interviewee in particular.

Although she was eighty-seven years old, Mrs. Furuta appeared to be in excellent health and possessed of a clear and vibrant mind. Like most Issei women, she seemed short by Caucasian standards. She wore eyeglasses, which heightened her dignity...she was attired in a pink dress, over which she wore a purple sweater. On several occasions during the interview, she "hopped" up from her chair...to fetch Japanese tea (ocha) and Japanese rice crackers (senbei) for Mrs. Gamo and me. The only indication that she was in any way hampered by age came from her remark that up until the current year she regularly traveled to Los Angeles--some forty miles away--to cheer on her beloved Los Angeles Dodgers baseball team at Dodger Stadium.

Mrs. Furuta soon evidenced she could both understand and speak English quite well; in fact, she sometimes launched into her response to my English-language questions without waiting for Mrs. Gamo's Japanese translation. The Furuta home stands quite near to Warner Avenue, now a very busy thoroughfare; the interview with Mrs. Furuta was conducted under less than idea sound conditions.

We were delighted with our interview session with Mrs. Furuta. She spoke movingly and in depth about... the immigrant Japanese experience in Orange County. She had so much to say in this regard, that it was necessary to schedule a follow-up interview session with her.

Next in Part 4 of 4 Voices from the past: Arthur A. Hansen discusses his interviews with Rev. and Mrs. Kikuchi, Henry Kiyomi Akiyama, Yukiko Furuta and Clarence Nishizu.

ABOVE: Wintersburg Japanese Presbyterian Church congregation, circa 1926, the year Princeton-educated Rev. Kenji Kikuchi came to Wintersburg. © ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

© All rights reserved. No part of the Historic Wintersburg blog may be reproduced or duplicated without prior written permission from the author and publisher, M. Adams Urashima.

Wednesday, February 8, 2012

All rights reserved. No part of the Historic Wintersburg blog may be reproduced or duplicated without prior written permission from the author and publisher, M. Adams Urashima.

Sanctuary for a century

The Erasure of Community History

At the onset of World War II, most Japanese Americans did not own their homes or places of business due to discriminatory early 20th-century laws restricting Asian immigrants’ rights to own property. Few Nihonmachi were able to regain their pre-war vitality, and many suffered yet again from urban renewal programs in the 1960s that destroyed what was left. The erasure of community history was one of the many painful legacies of forced removal and incarceration of Nikkei...

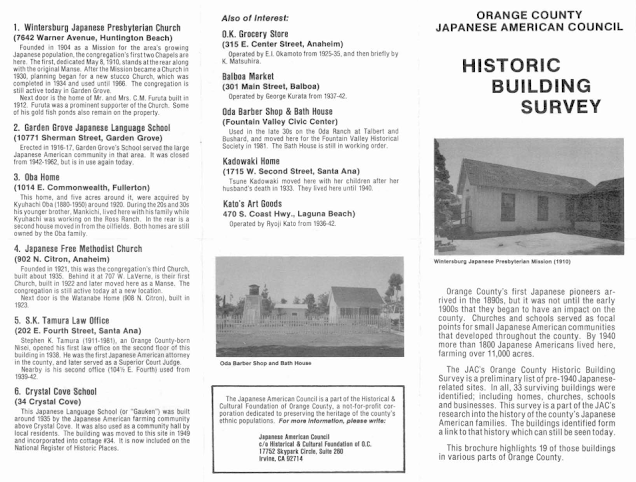

1986 Survey of Orange County's historic Japanese American sites

The front side of the Orange County Japanese American Council's 1986 "Historic Building Survey" includes the Wintersburg Japanese Presbyterian Mission as the featured property.

The majority of Japanese American historic buildings listed on the 1986 survey have since been lost to demolition, neglect by present-day property owners, vandalism, fire, and redevelopment.

See the brochure at http://www.huntingtonbeachca.gov/files/users/library/complete/080221-5.pdf

The 1912 Furuta family home, circa 2007, facing what once was Wintersburg Avenue, now Warner Avenue. The second Furuta family home--the 1947 ranch house off Nichols Lane--was built post-WWII incarceration. The windows of the 1912 Furuta home are boarded up in this image, although there is still a hint of the meticulously maintained gardens. The carefully manicured boxwood hedge were removed by the current property owner, Rainbow Environmental Services. Update: as of 2014, the property owner is Republic Services due to their purchase of Rainbow Environmental Services.

© ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

© All rights reserved. No part of the Historic Wintersburg blog may be reproduced or duplicated without prior written permission from the author and publisher, M. Adams Urashima.

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)