In the early 1900s, the entire country seems to have been enamored with celery. Celery was the super food of the early 20th Century, its promoters promising good health and weight loss. Early vegetarianism advocates were recommending recipes chock full of celery. And, in Wintersburg Village, farmers were toiling to meet the demand.

"In the peat lands celery can be grown in beds and by June the plants are ready to be set in fields. The plants are pulled, the tops trimmed to make the celery more bushy, then the roots are set in deep furrows. Boys and girls can help do this work." (Probably not an opinion shared by the men working long hours in the celery fields).

Miss Pearl continues, "Celery is carefully cultivated. As the plants grow, the dirt is gradually filled in the furrows. When about ready for market, the dirt is banked around the celery nearly to the top, where it is left for about two weeks to bleach.

LEFT: "Loading crated celery on to the cars." Long lines of wagons loaded with celery were a common site at the railroad sidings in Smeltzer and Wintersburg Village. Imagine the countryside smelling that strong, green scent of phthalides during the celery harvest. Scientists in the 20th Century determined celery contains the pheromone androsterone, which has an aphrodisiac effect for men. This might have made life easier for pioneer farmers when they tracked their muddy shoes into the house. (Image, June 1902, San Francisco Call)

The stalks turn from dark green to a creamy white. Then the field is plowed and the roots are cut with a celery cutter. Men trim and crate the stalks and then the celery is sent to market."

"The peat lands have been low and swampy, but when they are drained and cultivated they are very rich. Here in California, they use peat shoes on the horses. The shoes are made of square boards that are fastened on horses' feet to keep them from sinking in the damp soil."

ABOVE: "Horses wearing clogs at work in the peat lands." The peat soil was so soft, horses would sink into it without special wooden "peat shoes". The soil was easily plowed, water was plentiful, and Smeltzer became a "celery king" town. (Image, June 1902, San Francisco Call)

"The white plume and golden heart varieties of celery are most generally raised. The golden heart is a self bleacher. A celery field is a beautiful sight, with its long, straight rows of green plants,"concluded Miss Pearl.

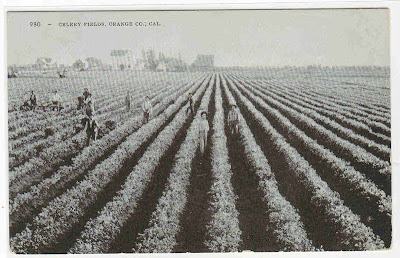

RIGHT: A postcard image of workers in the celery fields near Smeltzer and Wintersburg Village, undated. Arriving by 1900, many of the workers in the celery fields were immigrants from Japan, living in labor camps in Smeltzer and Wintersburg Village. By 1902, clergy began walking into the celery fields to talk to the laborers and the movememt to establish the Wintersburg Japanese Mission began.

A couple months later in November 1905, the Los Angeles Herald headlines shouted, "Peat Lands Now Worth Hundreds of Dollars an Acre." The Herald reported, "One of the most interesting sights in western wonderland is that of the celery trains which roll out of Smeltzer" (note: Smeltzer is in present-day north Huntington Beach, the Southern Pacific Railroad line carried celery freight from Smeltzer and Wintersburg to markets beyond).

RIGHT: A postcard image of workers in the celery fields near Smeltzer and Wintersburg Village, undated. Arriving by 1900, many of the workers in the celery fields were immigrants from Japan, living in labor camps in Smeltzer and Wintersburg Village. By 1902, clergy began walking into the celery fields to talk to the laborers and the movememt to establish the Wintersburg Japanese Mission began.

A couple months later in November 1905, the Los Angeles Herald headlines shouted, "Peat Lands Now Worth Hundreds of Dollars an Acre." The Herald reported, "One of the most interesting sights in western wonderland is that of the celery trains which roll out of Smeltzer" (note: Smeltzer is in present-day north Huntington Beach, the Southern Pacific Railroad line carried celery freight from Smeltzer and Wintersburg to markets beyond).

"Seventeen carloads celery are now sent forward, bound for the large cities of the east," continued the Herald. "Three thousand seven hundred and fifty dollars are the figures at which these daily shipments are valued and so heavy is the demand for the Thanksgiving trade that there is much doubt as to all of the orders being filled."

LEFT: Charles Furuta driving a wagon load of produce up the Southern Pacific Railroad siding near Wintersburg and Smeltzer, circa 1915. Similar sidings along the Southern Pacific Railroad allowed the growing agricultural community in Orange County to reach markets around the country. The Los Angeles Herald reported the December 1904 shipments "increased to such an extent that the Southern Pacific put on a special celery train from the fields in Smeltzer to Los Angeles, where the vegetable is routed to the east." (Photo courtesy of the Furuta family) © All rights reserved.

The Herald extolled the peatlands, albeit with a bit of a back-handed compliment, "When one considers that it was by chance this great industry was started, the contrast of ten years ago from today, is amazing. Before that time the peatland section of Orange county was considered both useless and dangerous and was inhabited by a low class of Americans who earned a livelihood by selling the peat cut from their lands."

Useless, dangerous and low class in the late 1800s. Okay. But, look at Orange County now (the Herald, a pro labor newspaper from William Randolph Hearst, published its last edition in 1989).

RIGHT: A crate of Dr. Brown's Cel-Ray soda near two of Wintersburg Village's prime crops--celery and chili peppers--at the Historic Wintersburg re-creation of the Tashima Market at Holidays in Huntington Beach at the Newland House Museum. (Photo, M. Urashima, December 2015) © All rights reserved.

"The peatland, formerly worth less than $5 an acre, now readily brings $200 and often rents for $40 an acre for the one crop," reports the Herald, noting that 3,000 acres were planted in celery---making the Orange County celery fields one of the largest in the world---and that "undoubtedly the production will be much larger in 1906."

By 1905, the farmers had formed the Celery Growers' Association, which organized the final cultivation, blanching and irrigation, as well as the "cutting, tieing, crating and carloading." Growers netted about 15 cents a dozen celery plants, which the Herald reported was a "handsome profit" since the cost of production was $50 to $60 an acre.

Something tells us the farmers of Wintersburg and Smeltzer weren't the only ones making a handsome profit.

ABOVE: "During these spring months, everyone is threatened with many complaints and diseases. These months allure to exposure, overwork and risk of health. Prudent people take advantage of the marvelous invigorating power of Paine's Celery Compound." (Los Angeles Herald, circa 1905)

ABOVE: Dr. Brown's Cel-Ray Soda is still found today. Reportedly brewed up by a doctor in 1869 in Brooklyn, New York's Jewish community, it was billed as a tonic of celery seeds and sugar to help children with digestion. Cel-Ray was the first Kosher soda and has a "lightly sugared, vegetable flavor of celery with a slightly peppery fizz that has been the favorite soda to pair with Deli foods from pastrami and corned beef to Kosher hot dogs and knishes." (Photo, sodapopstop.com)

Editor's note: Dr. Brown's Cel-Ray Soda can be found online at www.sodapopstop.com and sometimes at Huntington Beach's BevMo!, 16672 Beach Boulevard, between Warner (Wintersburg) Avenue and Edinger (Smeltzer) Avenue, an area once surrounded by the celery fields of 100 years ago. Cel-Ray tastes like celery and black pepper, a little like drinking Thanksgiving dressing.

All rights reserved. No part of the Historic Wintersburg blog may be reproduced or duplicated without prior written permission from the author and publisher, M. Adams Urashima.

All rights reserved. No part of the Historic Wintersburg blog may be reproduced or duplicated without prior written permission from the author and publisher, M. Adams Urashima.

Nice job with this research!

ReplyDeleteThanks, Paul!

Delete